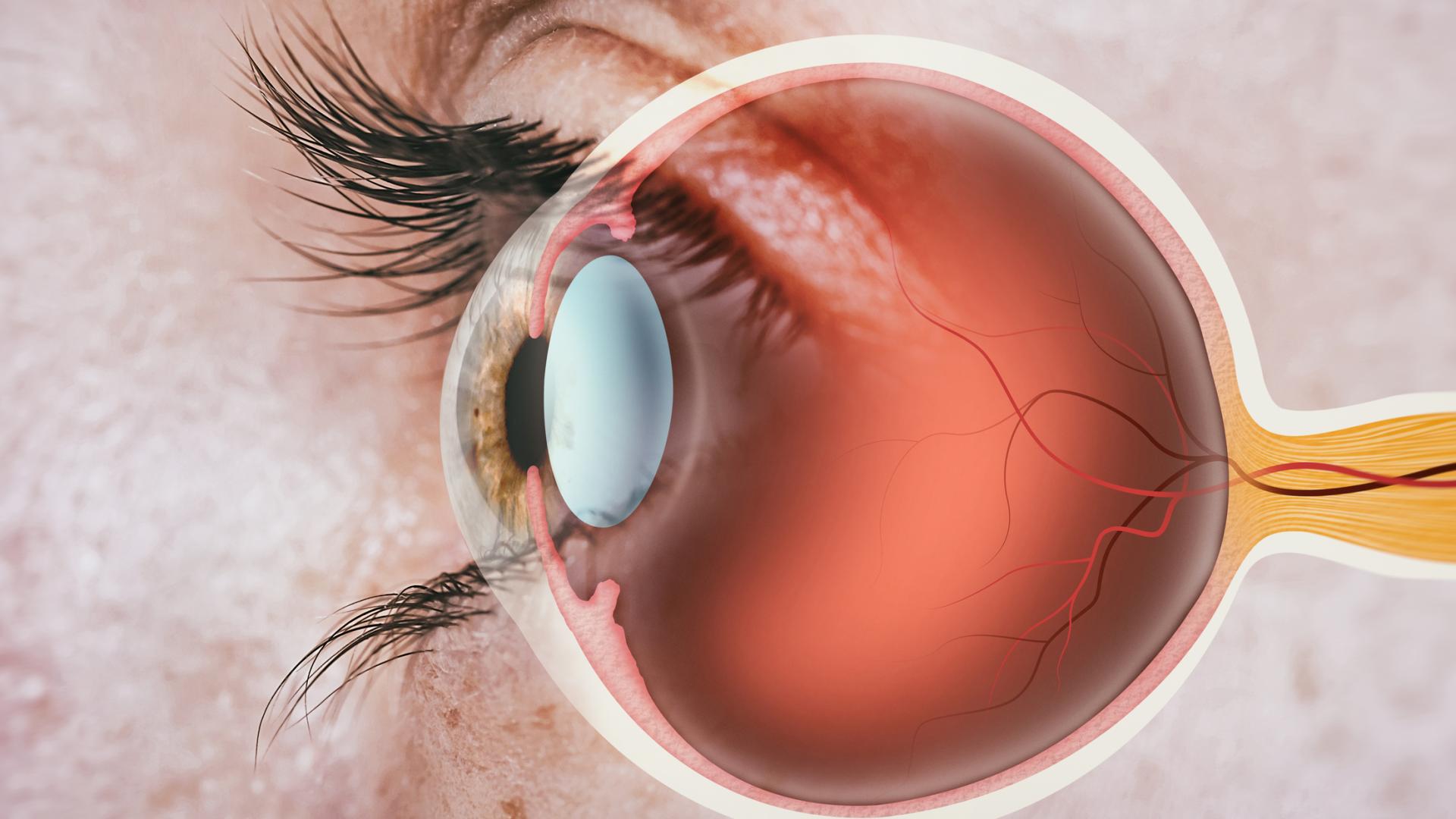

Glaucoma Chats

Glaucoma Chats are a series of free audio conversations with glaucoma specialists and other eye care professionals discussing the latest advancements in glaucoma research, treatment options, and day-to-day management strategies. Presented by National Glaucoma Research, a BrightFocus Foundation program, and the American Glaucoma Society.

Register

Upcoming Glaucoma Chats

Coming Soon!

Wednesday, January 14, 2026

1:00 pm EST (please adjust for your time zone)

Featuring: TBD

Free, Accessible & Interactive

Learn tips for living with glaucoma, the latest treatments, and promising research on the horizon.

Two ways to participate:

Receive a Call

Receive an automated phone call at the time of the Chat.

Stream Live on Your Device

Stream the audio live on your computer, tablet, or other device.

Catch Up

Missed a Glaucoma Chat Episode?

Recordings and transcripts are available for each episode of Glaucoma Chats.

Supported by:

Glaucoma Chats is presented in partnership with the American Glaucoma Society.