Download PDF

NANCY KEACH: Welcome, everyone, on the Zoom and on YouTube. My name is Nancy Keach. I am the Senior Vice President for Strategic Partnerships at BrightFocus Foundation. BrightFocus is a nonprofit that funds research globally. We’ve been around for 51 years and have funded over $300 million of research for Alzheimer’s disease, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. And we’re delighted to be bringing you today. We’re at almost two years of doing this program now, and we have another spectacular expert with a great topic to talk about today.

So I’ll also want to thank our sponsors of the program, Lilly, Genentech, and Biogen, for making this program possible, in part with educational funding. So thanks to those groups. And I’m going to jump right in. And we did receive, I think, close to 100 pre-submitted questions. And some of your questions won’t be answered today because they’re not on this specific topic, but I want to refer you to our website, brightfocus.org/zoomin, where we have all of the previous episodes there for you to look at.

So if you’re interested, for example, in what is the new drug Leqembi or how will genetics impact the possibility of getting Alzheimer’s? We have two episodes entirely on genetics. So you can see the list here. Feel free to access those.

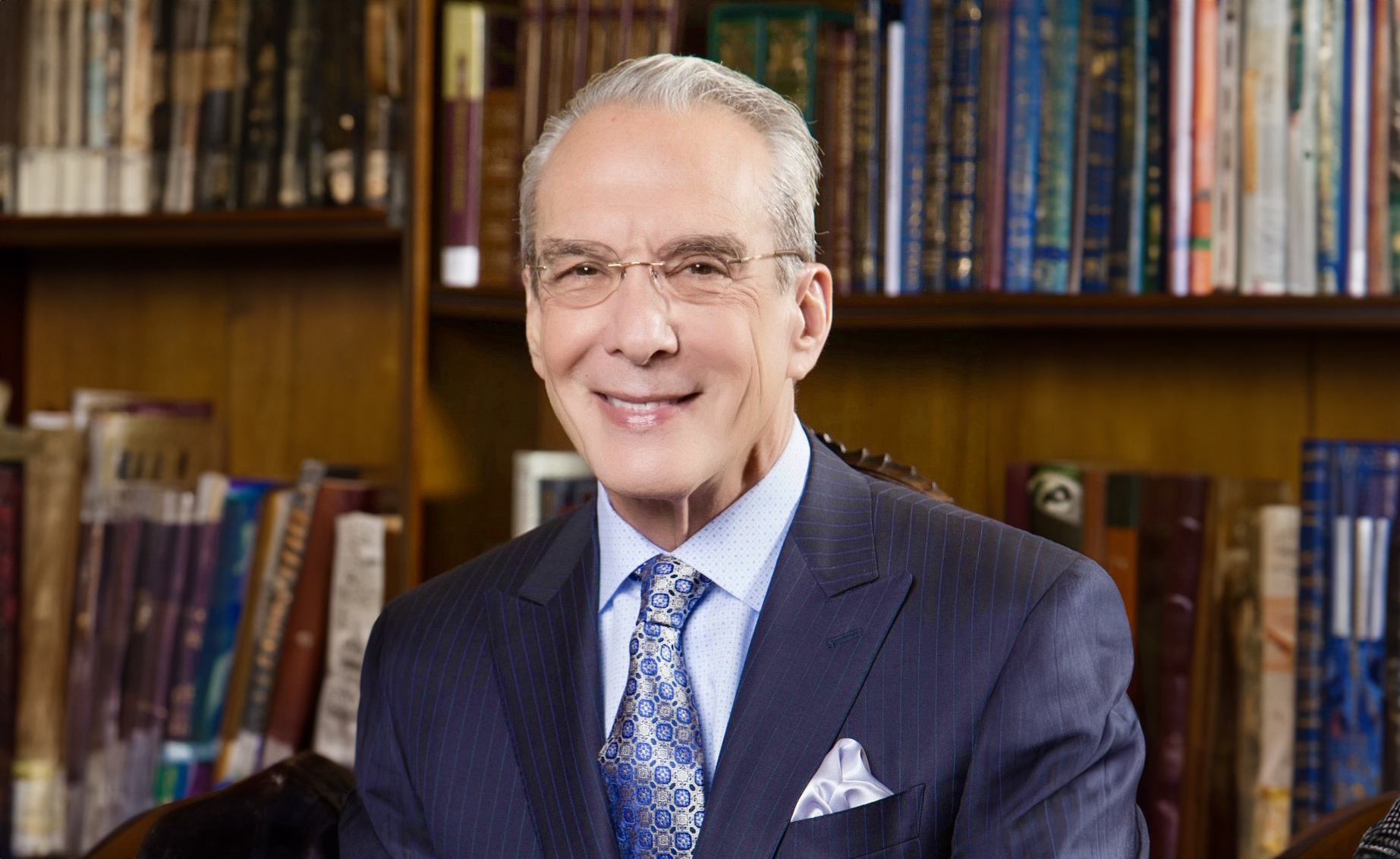

So I am absolutely delighted today to introduce Dr. Mike Weiner, who’s– so I’m going to embarrass him, but one of the giants in our field for sure. Dr. Weiner is Professor Emeritus of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, Medicine, Psychiatry, and Neurology at University of California, San Francisco. He has been conducting research for more than 60 years, even though he looks like he’s only 60, and is principal investigator of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, which is referred to as ADNI. And he is also principal investigator of UCSF’s Brain Health Registry, brainhealthregistry.org. And we will put that in the chat for you. Dr. Weiner has received numerous honors, including in recent years, the Nancy and Ronald Reagan Award and the Henry Wisniewski– I’m sure I’m pronouncing it wrong– Lifetime Achievement Award in Alzheimer’s disease research from the Alzheimer’s Association, and the Potamkin Prize of the American Academy of neurology, just to name a few. Welcome, Dr. Weiner. Mike, it’s great to see you.

And we’re going to do something a little different today. I think for those of you who are return viewers, you know that we usually don’t have our scientists put up slides, but Mike has about five slides we’re going to put up just to get our conversation going. But before I put up the slides, so our topic today is New Technologies for Early Detection of Alzheimer’s.

So Dr. Weiner, Mary Lou from Shalimar, Florida, sent in a question. Why is it important to diagnose early when a cure is not yet available? And Jill Cloverdale, Indiana, how can you stay on top of the disease when you have watched five members of your family die from it? I am scared. So you have people scared to get a diagnosis. We want people to get an early diagnosis. Why is this so important?

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, from a very practical point of view, there’s two FDA-approved drugs, lecanemab and donanemab, which remove amyloid plaques. They’re monoclonal antibodies. And all the evidence suggests that the earlier that people are put on these medications, the more effective they are. So that’s a huge reason that if there’s any concern about the development of cognitive decline or memory problems, that that individual will get a workup quickly to see whether that’s due to Alzheimer’s, which we defined as amyloid and tau pathology. That’s a simple answer.

There’s another reason, and that is that there are some prevention trials going on now. Prevention trials mean that they are enrolling people who are completely cognitively normal with no complaints, but they have evidence of large amounts of amyloid in their brain. So they have essentially early Alzheimer’s disease that has not yet produced any symptoms. And these prevention trials are designed to test the idea that treating somebody with an antibody that pulls amyloid out of the brain so early that they don’t even have symptoms yet, it will delay the development of symptoms. We don’t have the answers to those trials yet, but we expect the Lilly trial to give an answer by the end of this year. And there’s a lot of expectation or hope in the field that these are actually going to be successful trials.

If that is the case, then identifying people very early, meaning anybody over the age of 60 who has high levels of amyloid in their brain, would be a candidate for prevention treatment. And so that’s another reason to get on this early.

NANCY KEACH: And so thank you. That’s awesome. And before we go to your slides, what’s the name of the Lilly trial you just mentioned?

DR. MIKE WEINER: It’s called TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 3.

NANCY KEACH: And then they have another one, I think, that’s TRAILRUNNER.

DR. MIKE WEINER: TRAILRUNNER is just getting started. That is a new trial that if people are concerned, they have a strong family history, they ought to check out Lilly’s TRAILRUNNER because they are enrolling. The other two big trial– there’s another trial called AHEAD, which is the Eisai trial, but they’re not enrolling anymore. But the TRAILRUNNER’s just started enrolling, so there ought to be space in there for those who want to.

The risk seems to be very low in these trials, the risk for the so-called side effects, because people who are cognitively normal just have less amyloid in their brain and there’s less side effects. So we could talk more about this later.

NANCY KEACH: Sure. And I know we’ve talked about this a lot on the program, but for anybody who’s new, when Dr. Weiner is talking about amyloid or tau, these are proteins that build up in the brain that seem to be prevalent and associated with the loss of cognition or cognitive decline. And the drugs, the new drugs that have been approved, remove amyloid or lessen the amount of amyloid in the brain. So that’s the protein in the brain. So just probably most of you, if you’re online and trying to keep on top of these things, have heard of these terms but don’t want to take it for granted.

DR. MIKE WEINER: I know you’ve heard of the plaques. The plaques are made up largely of this amyloid.

NANCY KEACH: OK. So before we start diving into the new technologies, I’m going to let Dr. Weiner give a short presentation on some of the ideas of why these new technologies are being born, what they are, and some things he’s working on specifically. And then we’re going to get back into some of the more general things. So I’m going to turn it over to you.

DR. MIKE WEINER: Great. There’s a lot to be learned. So I don’t want to downplay research. We need to develop improved diagnostic tests. We have pretty good tests now, but they need to be improved and some of them are not FDA approved. But of course, most important is to develop effective treatments and preventions. But you can’t do that without understanding the causes and developing the diagnostic test. Next slide.

So what are the major obstacles which slow our– basically, it’s really– it comes down a lot to money because all this research is very expensive. And how can we reduce the cost of all this? Well, try to develop new technologies which are low cost. Well, what are the major new technologies? Well, first of all, we have the brain scans. Now these are not so new. These are within the last decade. But these have really revolutionized Alzheimer’s diagnosis. We can now diagnose Alzheimer’s disease in people who are alive. It’s routine these days. But back when I started, you could only really make a good diagnosis by using an autopsy information. So that’s a little late. The blood tests, there are new blood tests now for Alzheimer’s disease, and they seem to be diagnostic, and they are less expensive and very much more scalable than the scans are. But they are currently not FDA approved.

So one of the tests, the Lumipulse test of the Fujirebio, a Japanese company, they’ve submitted application for FDA approval. We’ll see what happens. But I think within the next several years, we’ll have FDA-approved tests, which are in the clinic. There are so-called CLEAR approved tests, a number of them. C2N is a company that has a very good test, but the bloods have to be shipped to St. Louis for analysis, and that it slows it down a little bit. But it’s a very good test.

So then there’s digital technologies and the internet. And more than 10 years ago, we created brainhealthregistry.org. And if you’re interested, you can go to that website and you could sign up and join that study. It’s an online recruitment assessment and longitudinal monitoring, and we enroll people into clinical studies. So this is an attempt to find a scalable, low cost way to get people involved in research and do some assessments.

But now in recent years, this artificial intelligence revolution is beginning and it’s impacting our field. So let’s go to the next slide.

NANCY KEACH: And can I just ask you for the Brain Health Registry, you don’t have to be in the San Francisco area?

DR. MIKE WEINER: Oh, no. It’s around the world. It’s international. Anybody can join it. It’s in English and in Spanish. There’s a Latino Brain Health Registry. And you can join the registry and then there’s a battery of tests, including some online tests of measurements and anyway, I don’t want to pitch my own study too much, but it’s available to anybody who wants to do it.

But what I’m really excited about is what we call artificial intelligence voice robots or voice bots. So if you haven’t used chatbot GPT or haven’t tried it, or you could go to a YouTube video to see what chatbot GPT does, but it’s free. You can download it onto your phone. And chatbot GPT really has demonstrated that AI-powered conversational voice bots have the ability to interact with people in a meaningful way and answer questions.

So together with John Morris and Krista Moulder at the University of California and Pedro Pinheiro-Chagas at UCSF, our group, Rachel Nosheny is my close collaborator, we started developing what we call the Voice Clinical Dementia Rating, or the vCDR. So the Clinical Dementia Rating, it was developed originally at Washington University in St. Louis. It is the most widely used gold standard assessment tool used in Alzheimer’s research. It’s used for screening. It’s used for diagnosis. It’s used in clinical trials. And in fact, it would be used more in clinical practice, but it requires a trained interviewer. It takes considerable time to interview both a family member and a friend or a friend and the patient. So not just the patient gets interviewed, but somebody who knows the patients. It’s scored by clinical judgment, which introduces variability.

Previously, with our WashU collaborators, we developed what we call an electronic digital ECDR. But now we are developing an AI-powered conversational voice CDR, which automatically interviews the family member and the patient all completely automatically. So I want you to just listen to a recording of this automated voice bot talking to one of our scientists who’s pretending to be a patient. OK, let’s see what happens.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– Welcome to the UCSF Memory and Aging Center’s AI assistant. I’m here to ask you a few questions about your memory and thinking. This conversation will be recorded for research purposes. If you agree to participate, please say Hello. Otherwise, feel free to hang up.

– Hello.

– Hi. I’m an artificial intelligence agent from the Memory and Aging Center of—

DR. MIKE WEINER: What you’re observing is the computer code that is driving this whole conversation on the screen if you can see it.

– This conversation will help me better understand how to support you. Let’s take it slow and feel free to share whatever you’re comfortable with. Does that sound OK to you? Would you like to proceed?

– Yeah, sure.

– Great. Let’s get started. Have you had any problems with your health lately? Please let me know by saying Yes or No.

– Yeah.

– Thank you for sharing that. Have you had any problem with memory or thinking? Again, please respond with Yes or No.

– Yeah.

– It’s important to acknowledge these concerns. When did your memory or thinking problems begin? You can choose from less than five years ago, five to 10 years ago, 10, 15 years ago, 15, 20 years ago, or more than 20 years ago.

– Less than five years ago.

– Got it. Thank you. Is it a consistent memory problem or does it tend to be inconsistent? Please say Yes if it’s consistent or No if it’s not.

– Yes.

– Thank you for clarifying. Is this a change compared to how you were previously? Please respond with Yes or No.

– Yeah.

– I appreciate your honesty. Does the memory and thinking problem interfere with your daily functioning? Please let me with a Yes or No.

– Yeah.

– Thank you for sharing that. Now let’s do a little memory exercise. Please remember the following name and address for a few minutes. Repeat it out loud one time. First name, John. Last name, Brown. Address number, 42. Street name, Market Street. City, London.

– John Brown. 42 Market Street, London.

– Perfect. Thank you. Now please repeat out loud the name and address you just heard.

– Pedro Chagas, Market.

DR. MIKE WEINER: He is trying to demonstrate that he’s got an impairment, you see.

– Thank you for trying to recall that information.

DR. MIKE WEINER: You see, he’s trying to recall.

– How old are you? Please say your age.

– I’m 37 years old. Also, can I ask you a few questions?

DR. MIKE WEINER: This is interesting. Watch how it responds.

– Of course. Feel free to ask me any questions you have. I’m here to help.

– Well, why are we doing this?

DR. MIKE WEINER: We haven’t written a script to answer this question. This is coming out of the artificial intelligence.

– This can help us assess any changes or difficulties you’re experiencing and find the best ways to support you. It’s also part of a broader effort to contribute to research on memory problems and aging. Does that make sense?

– Yes, we can proceed. Thank you for clarifying.

[END PLAYBACK]

DR. MIKE WEINER: Yeah, I think that’s enough, Nancy. So I just want to make one observation about what you just heard. This is the beginning. This is just the beginning. This is a very early prototype. But what we do is we have a scripted set of questions for the Clinical Dementia Rating, which has been widely used. But what you heard was that the AI-powered voice robot responded in an empathic way, and when he asked the question, well, what is this all about? We didn’t have a script that described that. That just came out of the AI’s system that described what the study was all about. And I don’t know if you noticed, but sometimes when he gave an answer, which was not a correct answer, she would say, thank you for trying. And there’s another place which we didn’t get to where he says, I only have a high school education, and the voice robot says, don’t say only. Everybody’s journey is different. We didn’t put that in the script. We just essentially specified that the interviewer would be empathic.

So it is amazing to work with this. And this has got nowhere to go but better. So I just want to say that in my opinion, in the future, AI-powered voice robots, like this, are going to be increasingly used for patient interactions in the Alzheimer’s field and in neurology, and psychiatry, all of medicine. They’re going to be hugely valuable for education of the public because you’ll be able to have conversations and get your questions answered, for getting informed consent in a really good way. All kinds of assessments of cognition, mood, anxiety, depression, activities of daily living, for all kinds of neurological and psychiatric conditions, and all of clinical medicine, longitudinal monitoring over time, detecting side effects of treatments, communications between patients and medical staff.

These voice bots are being incredibly inexpensive. I think the cost for a half an hour to us is $1 for OpenAI’s costs. The voice bots will save money. They will be available 24/7. You won’t have to schedule them. And in my opinion, they’re going to provide better information and better service than human interactions because you won’t have to wait on the phone for half an hour to talk to a scheduler, or you won’t have to schedule appointments way in advance. They’ll be available like that, 24/7. So that’s, to me, what’s really exciting about this new technology for Alzheimer’s. So let’s open it up to questions from here.

NANCY KEACH: Yeah. And let’s take the slide down. And I just also want to mention that, like Dr. Weiner said, this is just the beginning of this technology. But it will save money. It will save time. It will also make getting a diagnosis more possible for millions of people who live in rural areas or aren’t near a medical center, aren’t near a neurologist. I mean, there are states that have only a few neurologists in the entire state. So I just wanted– this is part of why I’m very excited about this. And I do want to address one comment in the chat, which is clearly from another scientist. And he says, only a small subset of memory assessments are voice-only. This technology would miss significant memory domains. But what I imagine you will respond to that and what I would say is, I don’t think anyone is arguing that this would be the only test that somebody would do, but that as a tool that’s currently being used in the arsenal of getting a diagnosis, this would be highly preferable to the way it’s being done now.

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, and there are also ways of using the camera and using the screen, so to display things visually for visual tests, and also using the camera, people give permission to have the camera activated, you can get a lot of nonverbal communication. I’m not saying this is going to replace human assessment. I’m just saying it’s going to aid it. It’s going to make it easier. It’s going to be good for screening, for scheduling. It’s going to really help us. Lots of interesting developments coming.

NANCY KEACH: I think it’s exciting. And this is obviously not the only technology we’re going to talk about today, but I’m going to jump to a question. And again, if anyone wants to ask a question directly, go ahead and put it in the chat or raise your virtual hand. But Susan in Woodbridge, California, wrote, if diagnosed early enough, so if you get these assessments early enough, can the progression to dementia be stopped? And if so, what are the most important signs to watch for?

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, right now, we don’t have any evidence that the progression is stopped. Well, perhaps in some cases, it is stopped. And in the large clinical trials that have been done of donanemab and lecanemab, and also of another treatment, aducanumab, which is not available anymore, the treatment in the group, in the hundreds of people who were studied, the treatment was the rate of progression was slowed by about maybe 30%.

But there are some people who benefited very strongly and other people who didn’t benefit that much. And the data suggests that the earlier the people were started, that is the less impaired the people were, the more that they benefited. But we don’t have evidence right now that in a substantial fraction of people it is stopped. So there’s a lot more to be done. We’re just at the beginning of this, but it is definitely the treatments are slowing decline.

NANCY KEACH: So when should somebody go to get tested? Because we were talking about the fact that these proteins can build up in the brain even before there are symptoms, or you may have mild symptoms and I have a situation with my cousin right now and her husband just got diagnosed with MCI and the neurologist said, well, just come back in a year. And to me that, that’s due to a lack of knowledge, but that means a year later, you’re going to just have progressed more without being part of a trial or trying a drug that could only intervene early. So when should people in general get tested? And most of the people on here are worried because they have someone in their family that’s had it.

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, I think as soon as anybody– certainly, I would say, as soon as anybody feels that they or one of their loved ones is showing signs of a development of a problem, then that’s the time. If you think that there’s a problem that has developed, that is, if your memory is not the same as it was a year ago, there’s some evidence of a progressive problem, certainly once you go to a memory care specialist, not just any physician, but a memory care specialist and get a workup.

And the workup, depending on the nature of it and how– well, the clinical judgment should include, ultimately, some evaluation for whether or not they have high levels of amyloid in the brain. Right now, the gold standard way to do that is with an amyloid PET scan. But the blood tests are increasingly used as a screen for that. And the blood tests are relatively inexpensive. So getting a clinical evaluation and a blood test, it’s not that expensive. It’s covered by insurance. And that’s what I would recommend. That’s kind of the beginning of whether or not somebody would be treated with one of these new treatments.

As Nancy was mentioning, she has somebody who has mild cognitive impairment. Well, if somebody’s been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, then the problem is sufficiently of that magnitude to warrant that diagnosis. They’re not just considered to be a kind of a worried well person. And if they have amyloid in their brain, then they are a candidate for one of these monoclonal antibody treatments.

NANCY KEACH: I was going to jump now to blood tests and cerebrospinal fluid tests and so on, but there is a question from Claire on YouTube. How do you counter the argument that blood-based biomarkers, so that’s seeing the proteins in the blood, are going to replace the need for other biomarkers, and that funding is not needed for research on other biomarkers? I’m not sure I fully understand it. Maybe you do.

DR. MIKE WEINER: Oh, I think I understand what they’re saying. But the current tests are pretty good for understanding amyloid in the brain. They’re not very good for predicting how much tau is in the brain. And that is an important predictor of cognitive decline. It’s an important predictor of the clinical stage. There’s a lot more research needed in these tests. And, unfortunately, we don’t have that much data on how the tests perform in people who are, let’s say, poor people, people with low socioeconomic status, people who don’t have health insurance.

But half the population of the United States over age 65 has a high school education or less. But most of the people involved in clinical research right now, who are as volunteers, are more highly educated people with higher socioeconomic status. There’s a lot more dementia and cognitive decline in the lower socioeconomic status population and we need to learn much more about how the tests perform there. So that’s just one example of some of the research that needs to be done.

The blood tests are pretty good, and I’m hoping that there will be FDA approval of some of the blood tests soon. That’s going to really enable their widespread use. As I said earlier, I think within a couple of years, every hospital will have some of these tests available and they’ll get more into primary care. And hopefully, if the treatments are good for prevention, that’s going to be the big impact on the population.

If you just look at a group of– well, I have one of the largest studies on this and our data is available. We share all our data. If you take a group of people with an average age of 75, about 25% to 30% of the people in that group are going to have be amyloid positive in their brain. They’re going to have a high level of amyloid in their brain. And even though they’re completely normal, completely healthy, cognitively normal, highly functioning people, they’re going to have a high level of– about 25% to 30% of a high level of amyloid in their brain. Those people are much more likely to progress to MCI and dementia over the next five to 10 years than people who don’t have amyloid in their brain.

My mother had Alzheimer’s disease. She was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and she died with it. So I’m a participant in my own study. I’ve had all these PET scans and MRIs and I’ve had all these blood tests. I’m fortunate– I’m in my middle 80s now. I’m fortunate that my amyloid levels are low. It’s a relief to me. OK. If my amyloid levels were higher, I don’t really know what I would do differently. I live a very healthy lifestyle. I’m very active. I exercise a lot and so forth. But I would get into a prevention trial right away if I had a high amyloid level. I’d join one of the prevention trials because I would have the possibility of being treated in a preventative way. So that’s one practical thing that somebody can do if they have a lot of concerns.

NANCY KEACH: And I think everybody knows by now, I’ll take this personally, not for BrightFocus, but a huge supporter of participating in clinical trials and research and registries, not only because, as Dr. Weiner is saying, we need so much more research on these areas and on so much bigger swaths of the population, but as a patient, if you are enrolled on a registry or in a trial, you get such better care and information because you are being overseen by an expert. And so I couldn’t champion participating in research any more strongly.

I’m going to– just before we leave, while we’re still on blood tests and blood biomarkers, Sharon from Toronto, and this might be Sharon Cohen, wrote, are blood biomarkers being used more often now by doctors to confirm the presence of amyloid and tau biomarkers prior to prescribing Leqembi and donanemab? So it got to what you were saying. Is it being used in the doctor’s office more so?

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, I don’t have any information really about what the community of physicians is doing. And part of the problem is the blood tests are not FDA approved. So I think that for the most part, the blood tests are now being used in academic practices where there’s research being done and they have some of these tests set up in a research environment, or there are some physicians who might be seeing large numbers of patients knows about C2N and the shipping of blood samples to C2N for results. Quest also offers a test and a blood test for amyloid, but I can’t really say how well validated that is because they haven’t published anything about that. So maybe it’s a good test, maybe it’s not.

I think the use of the blood test is probably going up, but we need FDA-approved tests. And all major hospitals, in their clinical labs they have these big machines that are made by Roche and Siemens and Abbott and so forth, where all your routine labs are done. They’re all done by these automated– these are essentially robotic machines. And there are kits that go in that do your liver function and your renal function and measure all these things. And within a year or two, we’re going to have FDA-approved– I hope we’ll have FDA-approved kits. And then it’s going to be available, widely available. So it’s coming.

NANCY KEACH: And we had a lot of comparison-type questions, like are blood tests as good as cerebrospinal fluid tests? And then there’s questions about digital cognitive assessments. What digital cognitive assessments are on the horizon that can be used for screening? And I’m going to throw in, even though I’m asking you like three questions at once, would you recommend– at 65 in the US, you are entitled or the doctor can get reimbursed for an annual wellness visit. Would you recommend people ask their doctors for a blood test or a memory test at their annual wellness visit?

DR. MIKE WEINER: I think certainly a memory test at their annual wellness visits, or an assessment of memory, some assessment of memory, whether it’s formal neuropsychological testing or talking to family members, observing whether or not there’s changes. That’s probably just as valuable as some of these formal tests.

The problem with some of these memory tests is that people who are highly functioning to begin with– for example, the normal range of IQ is 120 to 80. So if somebody begins with an IQ of 120 and their IQ goes all the way down to 80, they’re still in the normal range. Well, imagine that you’re looking at– these cognitive tests essentially have that same kind of scale. So a family member who knows the patient well is, in fact, if the family member is a reliable person, is going to be able to give a lot of information as to whether or not there is a change. And that’s really the big warning sign, is the change.

I would not advise everybody over 65 getting a blood test now, a screening blood test for Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. But if somebody has a change in their memory, really developing memory problems, then a blood test is a good screen. The gold standard way to assess whether or not there’s amyloid in the brain is either an amyloid PET scan or a lumbar puncture to obtain cerebrospinal fluid. I think that there, is in the community, there’s some reluctance for people to have lumbar punctures or spinal taps, but they are not a big deal at all. I mean, any woman who’s had an epidural knows it’s not a huge, big deal. I’ve had five lumbar punctures as part of my study. I would rather have a lumbar puncture than a lot of dental procedures. It’s just– if they use the lidocaine so you don’t feel anything, it can be a little uncomfortable. It’s extremely safe. Your spinal cord ends many inches above where they put the needle, so there is no risk of any kind of spinal injury when you have a lumbar puncture. But it’s gotten into the culture because way back during the polio epidemics, people had lumbar punctures and then they sometimes had paralysis and there seemed to be an association in the minds of the public that the spinal tap was related to development of paralysis, which is definitely not the case. Extremely safe. So lumbar punctures are much less expensive than the PET scans, and there’s no radiation.

And in many places where there’s a backup of people for assessments for getting into the treatments, the PET scanners are rate-limiting because PET scanners are used widely for cancer diagnosis. And PET scanners are expensive and it’s a whole big deal to have a PET scanner. So there are a limited number of them. So in many places, like Washington University, they’re doing a lot of lumbar punctures. Some physicians are starting to use the blood tests alone to make decisions about whether or not somebody should get these treatments. I think it’s a little problematic, but that’s up to– it’s very much of a clinician decision.

NANCY KEACH: Got it. And what are the– this is Cyan from the UK. What are the digital cognitive assessments on the horizon that will be used for screening people?

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, there are many, many, many, many, many digital cognitive assessments. OK. Cogstate and Cambridge Cognition were pioneers in this over 15 years ago. And now there are probably hundreds of digital assessments on the internet. Some of them are tests where you can self-take your assessment. But the vast majority of these tests are not really very well validated, meaning that they haven’t been tested in clinical populations compared with other gold standard tests.

We have now something sponsored by NIH called the Mobile Toolbox, which provides digital assessments. I’m very much involved with this field. The Brain Health Registry has used Cogstate, we’ve used Cambridge, we’ve used MemTrax, we’ve used the Lumos test, which used to be popular. I can’t make any recommendation because I think that these are at the very best. Personally, I think at the very best now. They are some kind of a screen. And as I said earlier, the problem with using them as a screen, especially in the kind of people who are watching this video right now, is that people who are very, very high-functioning, they deteriorate, they’re going to continue to be in the normal range.

Now, there might be some value in picking a test that you want to take or that recommended by somebody or your physician and then start taking that test on a regular basis. Usually when people start taking tests and repeating the tests, you see them improve because of practice effects and people are getting more comfortable with the test and you kind of learn how to game the test. So I’ve looked at my own scores over the years and they go up and up. If you started seeing your scores going down, well, that would be a raise of concern and then I would go to your physician and say, I think I’ve got a problem. My scores are going down. And then you get involved with the workup there. But I’m not comfortable recommending any particular tests because, to be honest with you, I don’t see any evidence that one test is so much better than another.

NANCY KEACH: It’s interesting because I think the sense I’m getting, having been in this field now 16 years, is that just like with treatments, the idea that it won’t be just one treatment that’s a cure, but a combination of treatments that assist with different parts of different causes.

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, let me just say that in clinical medicine, it always comes down to clinical judgment. And doctors and people who are skilled in this field use all kinds of information together. It’s not just the test. No one test is going to diagnose MCI or dementia. And as I just want to repeat, so you get the self-report. That is what the patient says. Things have gotten worse. I used to be able to do this. I can no longer do that. That’s important information.

But the people are unreliable. A lot of people are in denial. They say, oh, I’m fine, but they’re totally demented. And some people are worried, well, oh, I’m really worried. I’ve got a lot of anxiety about it and I think I’m losing my memory. And you test them and they’re fine. There’s no evidence of a problem. So that’s why having a family member or a close friend, a spouse or a child, a grandchild, or somebody who can answer the question, has there been a change in this person over the last year, over the last two years?

And then in the Clinical Dementia Rating, which I showed the voice bot, what we do is we ask the friend or the family member, we call the study partner, to identify two recent episodes that the patient had, was involved with. They went out to a dinner, they went to a party, they went, they had a doctor visit or they went to a ball game or whatever. Two recent episodes. And then– that’s asked in private. And then they ask the patient, tell me about two recent episodes in your life. And then the interviewer tries to see whether or not the patient remembers the same details, what the weather was like, what people were wearing, what people were present. And the clinician judgment of a trained interviewer can say whether or not somebody is showing signs of a problem.

And this is the gold standard instrument for diagnostic categorization in clinical research, is the Clinical Dementia Rating, which is why we’re so excited about developing an automated voice bot that does that. But most physicians, the vast majority of physicians, will never do a Clinician Dementia Rating because it takes 20 minutes to interview the family member and 20 minutes to interview the patient in this way. And doctors and their staff just don’t have the time for that, unless they’re in highly specialized memory clinic settings.

NANCY KEACH: So I want to ask because I know earlier when I mentioned the trials, the Lilly trials, there was a bunch of immediate response in the chat. And we are actually planning to do some episodes coming up in our Clinical Research subseries of the Zoom Ins on those trials, specifically on those trials. But Mark from Elmhurst, Illinois, wrote, are there any clinical trials of these latest technologies, so the diagnostic technologies, that some of us with an Alzheimer’s history could tap into? So are there trials for diagnostics or the vCDR or anything that you could tell us off the cuff?

DR. MIKE WEINER: No, in our Brain Health Registry, we do studies of this, just in the Brain Health Registry. So if you’re interested in this kind of thing, you could join the Brain Health Registry. And the Brain Health Registry has the ability for a study partners to join. So we have 8,000 or 10,000 people in the Brain Health Registry who we have the participant and then we have a family member join so they can be tested. That’s the biggest ongoing study that I know of that looks at these kinds of diagnostic tests.

The pharmaceutical companies, when they’re doing their studies, will often include new diagnostic technologies in their trials. So that’s one way. But you have to enroll in the clinical trial. But if you’re particularly interested in this, just go to the academic center that is near you and go to the neurology department or go online and see what research studies are being done in your local community. Because there are all kinds of research projects going on that people are looking for participants to volunteer. And some of those will be blood test studies or studies of online assessments and so forth. But it’s very variable from one university to the next.

NANCY KEACH: And I will mention that on BrightFocus Foundation’s website, brightfocus.org, there is a clinical trial finder. So you can actually– of course, and I know Nina Silverberg is on the call here. The NIH has, NIH.gov has a clinical trial site that’s quite vast and you can try to navigate either of those.

DR. MIKE WEINER: That’s a memory test in itself.

NANCY KEACH: Yeah, it is a test in itself, which I’m kind of dancing around. So it is a little bit hard to find. We hope that the one on brightfocus.org, which uses the Antidote widget, is a little more user-friendly than some of the other ones out there.

So I can’t believe how we’re running out of time already, but this was a question that I thought was really interesting. Ruth Ann from Cincinnati, will these technologies be able to differentiate between who has markers/expressions but may not actually develop dementia? So I believe what she’s saying is will these technologies be able to differentiate if you have amyloid, that you may have the kind of amyloid that’s not going to lead to dementia?

DR. MIKE WEINER: That’s a really good question. And the answer is, a lot of progress has been made in that area. So this is what we call prediction. Basically what everybody wants to know is, if you’re normal, you want to know what is the likelihood that in three to five years am I going to develop mild cognitive impairment or dementia, let’s say, in five to 10 years?

And now there’s been a lot of work going on– Suzanne Schindler, who’s at Washington University, has done a lot. She’s not the only person working in this area but developing what they call the amyloid clock. So it turns out that if you know the level of amyloid in the brain from a PET scan and ideally, if you have two. So you can look at the rate of change of amyloid in the brain. But even if you know the level of– even if you know one level, that allows you to begin to do some prediction.

And there are, in fact, some websites. I think The Swedish Oscar Hansen study, they have a website, which I can’t speak to the value of it. There are a number of websites that claim that they can give you some predictive information. I would take it with a little grain of salt, but so far it’s been used kind of more academically and I haven’t seen data that in a real world it really works. But there is a lot of evidence that if you understand how much amyloid somebody’s got in their brain, how much tau somebody’s got in their brain, and what is their current level of cognition, that you can get a reasonably accurate prediction of what to expect over the next bunch of years.

So what you do with that information, though, that’s another issue. I mean, the question always comes back, to aside from these treatments which pull out amyloid from the brain, what else can I do? And the answer, I think, is really quite simple. And that is, it’s just live a healthy lifestyle. Most importantly, try not to smoke. Try to keep alcohol consumption at a minimum or at least at a reasonably moderate level. Avoid other bad drugs. It’s pretty obvious. Control blood pressure well. Your blood pressure, you try to keep your systolic blood pressure no higher consistently than 120. Get a home blood pressure cuff. Make sure your blood pressure is well controlled. Make sure that your lipids are well controlled. If you’re not on a statin, don’t resist being on a statin because you don’t want to take another pill. There is some evidence that taking a Centrum– taking a multivitamin once a day is beneficial. It’s weak evidence, but it doesn’t hurt to take a multivitamin.

The Mediterranean diet and the so-called MIND diets, which are basically low meat, high fish, green, lots of kale, green vegetables, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, all of that kind of stuff. You go to my refrigerator and you’re going to see kale, broccoli, Brussels sprouts at least one meal a day. The MIND diet emphasizes nuts, nuts and berries, fresh fruit servings. Basically it’s a healthy diet. It’s good for lots of things. It’s not just good for the brain, but I think you all know that. So avoid the ultra-processed foods to the extent possible. And there’s a lot of ultra-processed foods probably in your refrigerator right now. I can’t get my wife to give up her coffee-flavored yogurt that she loves, but it is ultra-processed. The English muffins are ultra-processed. So whole grains. I mean, all of this is out there. All of that information is out there. But exercise, regular exercise, regular– I personally believe daily exercise at least a half an hour a day of daily exercise, a lot of evidence that this is really good for you. Not just good for Alzheimer’s or dementia. It’s good for you in general, OK? It’s good for your mood. It takes your mind off some of the problems that we have to think about. So those are the things that you can do that are practical.

NANCY KEACH: And I think and sleep.

DR. MIKE WEINER: Getting the sleep you need. Getting the sleep you need. A nap in the middle of the day for seniors is just fine too.

NANCY KEACH: And the other couple of things I just would mention is keep on top of hearing loss and vision loss because those are both contributing factors too.

DR. MIKE WEINER: They’re associated with it. Yeah.

NANCY KEACH: Yeah.

DR. MIKE WEINER: I mean, being active socially, being involved engaged. But for some people, it’s easier than others.

NANCY KEACH: Right. So there’s four minutes left in the hour. I told you it would go by very quickly. So if anybody has a burning question that they want to ask, again, raise your hand or put it in the chat. But Mike, I think my closing question to you is one that came in from Jeff from Knoxville, Tennessee. It’s a little off-topic, but it says, can you provide information about the next three drugs likely to become available that are not anti-amyloid focused?

DR. MIKE WEINER: Yeah, I wish I could. I would say the class of drugs that I am most excited about are the GLP-1 agonists. The Ozempic, the Mounjaro, the Wegovy treatments, which were initially developed for diabetes then they turned out to be good for obesity. Now more and more evidence is accumulating that they are good for all kinds of things. They seem to be good for substance abuse problems and addiction issues. They tend to reduce cravings. But they seem to be good for general health. They seem to help blood pressure. And there’s a number of trials going on in dementia, cognitive impairment, and maybe even prevention.

So I think that not all cognitive impairment– only half of MCI is caused by amyloid, even in ADNI, even in well-educated people. So there’s a lot of cognitive problems that are not related to amyloid and tau, which is what we call Alzheimer’s pathology. So there’s a lot of work to do. If we’re going to eliminate mild impairment and dementia in our overall population, we have a long way to go and lots to do. And hopefully, the NIH will keep funding our research.

NANCY KEACH: And someone did ask a question about the impact of the limitations on funding, but I don’t want to get political here.

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, it’s not political. I mean, the Columbia Alzheimer’s Research Center has lost its funding. The Columbia University Alzheimer’s Center, which, by the way, is headed by a Israeli-American Jewish person. They are losing their funding because of Columbia’s reaction to anti-Semitic behavior on their Columbia campus. So there’s a lot of frightened academic people right now and we can only hope funds will continue to flow. Congress appropriated them and I think our representatives want to see NIH funded.

NANCY KEACH: Yeah. And we certainly do. And we will be, as a private philanthropy, also talking about the importance of private philanthropies outside of federal funding, and that it’s more important than ever to give to research. And I want to– since we have another couple of minutes, what can we do, we the people, so to speak, to help your team accelerate the development of the voice activated CDR and other innovative diagnostics? What can people on this call do?

DR. MIKE WEINER: Well, right now we’re seeking funding. And I would say you could donate to BrightFocus. That would be a help. But maybe BrightFocus is—

NANCY KEACH: I didn’t plan that, but that would be great.

DR. MIKE WEINER: We are seeking funding, though. We don’t have any—

NANCY KEACH: And I think joining the Brain Health Registry and getting into trials was kind of also where I was going with that. Any parting words? I know we only have one minute.

DR. MIKE WEINER: No, I think that for those of us who’ve been in the field watching the developments of this field, it’s just been amazing. 20 years ago, we didn’t have any tests for Alzheimer’s disease. We didn’t have any treatments. We couldn’t diagnose Alzheimer’s in living people. In the last 20 years, we’ve made amazing strides.

If you’re interested in, there is on YouTube Michael Weiner or you go to the ADNI website. I gave a plenary lecture in Philadelphia last summer. It’s a 20-minute talk all about the advances that have been contributed by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, but it really is a summary of what’s happened in the field in the last 20 years for diagnosis. It’s about blood tests and scans, and lumbar puncture tests, and the development of treatment. So it’s been amazing what’s been accomplished. And we have treatments that slow progression. And there’s lots more to do and it’s very exciting for us to continue to work in this field. And thanks so much for all of you joining this call.

NANCY KEACH: And I also want to mention that Dr. Weiner is a fabulous jazz musician. And if you want to hear him playing, what is the YouTube?

DR. MIKE WEINER: Mike Weiner Trio on YouTube.

NANCY KEACH: There’s a lot of scientists, believe it or not, who happen to be really great musicians, and Mike is one of them. So thank you so much for joining us today. And I want to thank the audience. I know you can’t tell, but I am watching you and looking at you and seeing when you smile and seeing what seems to make an impact. And that’s why we did this as a Zoom and not just a webinar where we don’t see you. So please feel free to write to us, talk to us, ask questions live next time. It’s perfectly fine.

And we’ll go to just a couple of closing slides. If you would like some free resources, here’s a list. Go to brightfocus.org/ZoomIn. These are print publications that we can either mail to you or you can download. And the next slide.

If you have suggestions for future topics, I could see that the new trials and drugs are of tremendous interest. You can suggest topics to us at reply@brightfocus.org.

And next slide, please. Here are the upcoming trials. I think on April 3, we’re going to have Dr. Michelle Papka who runs the clinical trial site, one of the very productive clinical trial sites, to talk through certain tests that are being done there. Actually, the HOPE study, which we had featured earlier, she is doing there, and that is happening across the country. And so we’ll profile that and some other studies on April 3.

And again, I just want to thank everybody for joining us. We at BrightFocus actually are very emotionally committed to our mission, to the mission of understanding and treating these diseases. And so thanks for joining us and have a great next month. Take care.

Resources: