BROOKS KENNY: Good morning and good afternoon, depending on where you are. And welcome to Zoom In on Dementia and Alzheimer’s Clinical Research. My name is Brooks Kenny. And I am an Alzheimer’s advocate and advisor to BrightFocus Foundation. I’ve been working in the Alzheimer’s field for more than 12 years. And I’ve been an advocate and have, as many of us do, my own personal family experience as a caregiver with this disease.

For those of you new to our monthly webinar, I want to give you some background. BrightFocus Foundation is a nonprofit organization that has invested nearly $300 million in research grants, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools in the areas of Alzheimer’s disease, macular degeneration, and glaucoma.

Today’s program is going to look a little bit different if you’re one of our regulars every month. Our focus here really is to zoom in on clinical research. And so we’re not necessarily going to focus on one particular trial. But we’re going to go back to basics and actually walk you through, what is a clinical trial? How do you get involved with one? What are the phases? How do you identify one for your loved one? So we have a lot of really great content to share with you today.

This program is supported in part by educational funding provided by Biogen, Genentech, and Lilly. And so we thank our sponsors for their support of this important work.

We have a fantastic expert guest with us today. And it’s a very compelling subject, which I know is of great interest because 650 people actually registered for today’s episode. And we received over 100 questions in advance. Many of the pre-submitted questions were on today’s topic, which we really appreciate, while some were not. And so we want to make sure we’re always reminding you that you can go to brightfocus.org/ZoomIn and on YouTube. And you can revisit any of our episodes. So you can see we have a wide range of topics that we’ve already recorded. And we make these free and available to our constituents and community here at BrightFocus Foundation. So we do encourage you to go back and rewatch episodes and certainly share them with others.

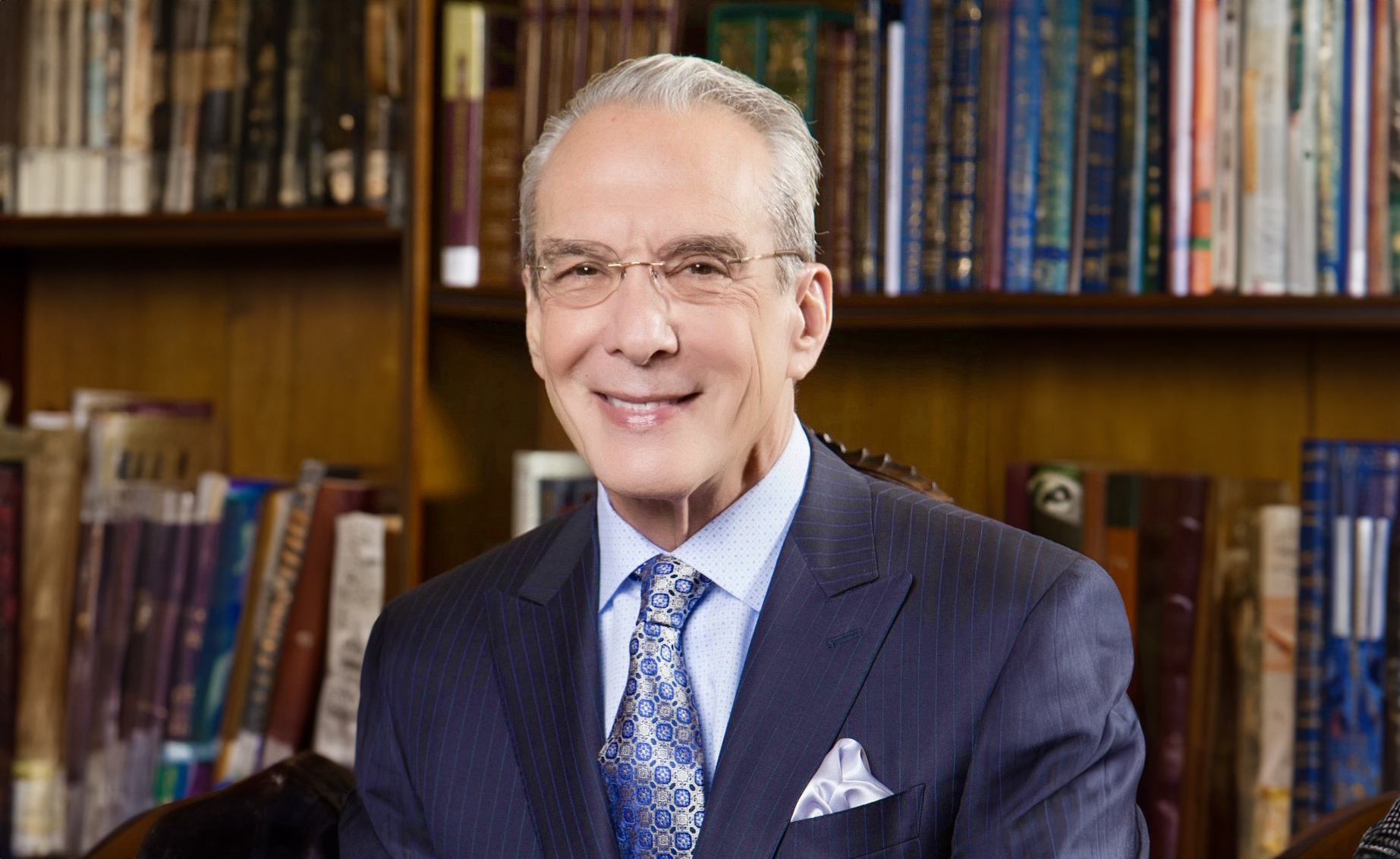

Well, now, I’m absolutely delighted to introduce today’s expert guest, Dr. Jeffrey Cummings. I have to say, I’ve had the benefit of moderating a session with Dr. Cummings one other time. So I can’t even believe I’m getting to do this twice in my career. So grateful. Dr. Cummings is the Joy Chambers-Grundy Professor of Brain Science, the director of the Chambers-Grundy Center for Transformative Neuroscience, and the co-director of the Pam Quirk Brain Health and Biomarker Laboratory at the Department of Brain Health at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He is globally known. Really, he is globally known for his contributions to Alzheimer’s research, drug development, and clinical trials. He has been recognized over and over again for his research, his leadership contributions in the field through many distinguished awards. He was formerly the director of the Mary Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research at UCLA and the director of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health.

If you have not heard Dr. Cummings speak before, let me just tell you, you are in for a real treat. He is internationally recognized. That’s true. I could read on and on about his credentials. But what I personally love most about him is that he helps us understand the complexities of the disease and the clinical research opportunities in very simple terms. It’s not an easy task. This is a complex ecosystem. And I think Dr. Cummings does it so well. And we’re pinching ourselves that you’re with us again today. So thank you so much for being here.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Brooks, it’s my pleasure to be here. I love talking directly to the people who are most concerned about this disease. So I am delighted to be invited to be BrightFocus’ guest.

BROOKS KENNY: Great. Thank you. Well, we’re going to get started right into the questions. But before we do, I want you to give us a general overview of where we are in clinical research and maybe highlight some of the innovation that has occurred. So much has changed even in the last five years in this space of Alzheimer’s. We’d love to hear your first take on where are we today in clinical research. Then we’ll get into explaining the basics. And we’ll get into people’s specific questions. But let’s get a level set.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Great. Well, I’ll tell you how I think about this because every year my group puts together an annual review of all of the clinical trials that are active on the first day of the year. And I’m showing you here the 2024 map because I have on my desk the rough draft of the 2025 map. And it has not yet been converted into some reasonable figure. And I just want to show you how active clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease are.

So last year, there were 164 trials testing 107 drugs. 107 drugs– those are chances and opportunities for new drugs to evolve for patients. I call this the Circle of Hope. Because each of these trials, each of these drugs is a new learning about Alzheimer’s disease and a new step forward in terms of therapeutics. Most of these drugs will actually not be approved because the failure rate of new therapies is high. But some of them will. So if you test many drugs, a few will be approved.

And I’ll just tell you a little bit about the Circle of Hope. So the inner circle there is the phase III drugs. So the phase III are the ones that are closest to being reviewed by the FDA. So the drug starts in phase I, progresses to phase II, and then progresses to phase III and to the FDA if it succeeds. So those drugs are quite far along in their process.

The middle circle, those are the drugs that have been tested in healthy volunteers and are now being tested in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. And they have a higher failure rate because they are more novel. And so that’s why that group of drugs is larger.

And in phase I are the drugs that have just been tested in animals that are genetically engineered to have Alzheimer’s disease. And now, they’re being tested in normal volunteers to make sure that they are as safe as possible. And then if they are, then they will go on to be treated and tested in Alzheimer’s disease.

Now, here is some really great news. And you are the first people to hear this, that we are looking, as I say, at our current report. So last year, there were 164 active trials. This year, there are 182 active trials. Last year, there were 127 unique drugs. This year, there are 138 unique drugs. So we see growth across the spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. And particularly exciting for me is we see almost a doubling of drugs in phase I. And that means those drugs will– some of them will be promoted to phase II and possibly eventually to phase III and approval.

So we’re seeing definite momentum in new drugs being tested for Alzheimer’s disease. And that’s why we want to talk about clinical trials today is because these drugs can only be advanced to the FDA if they’re tested in clinical trials. That is the kind of evidence that the FDA demands in order for a drug to be approved. So that’s why the linkage between the new therapies for you, for your children, for the rest of the world is so intimately linked to clinical trial participation.

BROOKS KENNY: Fantastic. I do have a follow-up question. Have you always called it that? I know you’ve used this model for years. Have you always called it the Circle of Hope? Or is that new?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: That is new. I did a presentation for Alzheimer’s Disease International. And they were calling it the Circle of Hope. And I said, yes, it’s the Circle of Hope. But I love that idea.

BROOKS KENNY: I love it too. It’s great.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: They started calling it the Circle of Hope because people before had been calling it the Wheel of Fortune. And I thought that, well, that’s too much of a gambling term. Let’s call it the Circle of Hope.

BROOKS KENNY: Yeah, it’s very appropriate, given where we are in the field. So thank you for that overview. The next set of slides I’m going to ask you to share with participants is really going back to basics– in the most basic terms. We want participants listening today and listening back to the recording to have an understanding of the basics– what a trial is, how do they get involved, what can people expect. And then we’ll get into some of the specifics. But I’d love to just have you walk through the next set of slides.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yeah, sure. Well, I wanted to start with the very basics of what is a trial. And I’m sorry, actually, that that was the word that was originally chosen. Because if you’re in a trial, it sounds like you might go to court. But of course, this is a totally different idea, that in order to understand whether a drug is working, we have to have it tested in humans who have the condition that we’re trying to treat. And so it’s an experiment. And it’s an experiment where we pay tremendous attention to the safety of the participants. We understand that participants– and we may have participants online. I hope we do. Participants are the citizen soldiers who are advancing therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. This is the only way to get new treatments to the FDA and possibly into the market.

So trials are an experiment to determine whether the drug is working against the disease that we’re trying to solve. And the trials have extensive safety monitoring and safety aspects that we might talk more about. But basically, it is an experiment to determine whether a drug is working or not. And that’s why it’s so important.

So what is a trial? And I’m just going to walk through a few slides here to– but please put your questions in the chat. And Sharon will help us understand those. But I just wanted to reassure you about some of the things about the safety and the appropriateness of a trial. So a trial has to be reviewed by an institutional review board. So it’s not just that the investigator wants to look at this drug. It is that the investigator has to put together the protocol. And that protocol has to be reviewed by a neutral external body. In the universities, that may be an external– the IRB of the university. But increasingly, we use central IRBs that are professionals in reviewing these. And they have to approve the trial before it can be conducted locally.

Then perhaps you’re in the clinic with a doctor. And he or she suggests that you participate in the trial. And the patient and the legal guardian, if there is a legal guardian, must give permission to participate in the trial. It’s not that the doctor can just write a prescription for a drug that he or she wants to understand and test it. That can’t be done. You must be informed that a clinical trial is available and whether or not you want to participate in it.

There is no charge for participating in the trial. This is research. It’s not care. And there is no charge. So, if you get a solicitation for a trial and it asks you to pay for participation in the trial, you should regard that solicitation with great skepticism because legitimate trials are free. We’re trying to get this information. And we greatly appreciate the participation of patients and their families in trials.

In some cases, and increasingly so, participants might be paid at least for their expenses, transportation expenses, the time that they spend– patients and families spend a lot of time if they’re in trials devoted to things that the trial needs. And of course, there are blood draws. In some cases, there are lumbar punctures. There may be brain imaging. All of this requires time. And I think we show our respect for the patient’s time by compensating for that time. And increasingly, trials do that. And you can ask about it when you are considering a trial.

Now, the amount of payment is, again, scrutinized very carefully by the IRB because a trial that was paying a lot might be seen as manipulating the participant to come into the trial for payment. And we don’t want that. We want the doctor and the patient to be allies in developing new therapies, not like an employer-employee relationship where the patient is paid. So we compensate for expenses. We compensate for time. And we’re careful about how that’s viewed.

A participant can withdraw from a trial at any time for any reason. So if you feel like it’s just too much time, you can stop. Or if you feel like your spouse is ill and you need to be there in order to take care of he or she, then you can stop for that reason. You can stop for any reason. But of course, we want people to continue to participate. And to understand the drug over time is very important. So we try to keep people into trials. But one should never feel that you’ve been drafted into the army and you can’t leave. It’s not like that at all. You’re voluntarily participating every time you go to the trial site or do something else for the trial.

All trial-related information is confidential. So of course, the sponsor of the trial knows this. The doctor knows this. But no one else does. So trial information is kept completely confidential. It could never impact your insurance, for example, if you were participating in a trial. That would never become known by the insurance company. So I think the confidentiality is very important.

And a lot of people ask– and I think this is important, and we’re trying to come to better terms with this– is people say, well, will I know whether I got the drug or not? I know that there was a placebo in this trial. And I want to know whether I was on the treatment or not. And the blind, where the doctor and the patient do not know whether they’re on drug or placebo, is not broken until the last patient is done with the trial. So that may be two years after you finish the trial, when the last patient completes the trial. And then increasingly, we are trying to make sure that the patients and families do get this information. I think we’re still imperfect at this. But I think it’s really important that you know whether you are on the drug or the placebo. And there is, in many cases, an extension of the trial after the double blind period where we give everyone the drug. So that’s not true of every trial. But it’s true of most trials that there is an open label extension, meaning both you and the doctor know that you are now getting the drug. It cannot be any other way. So that is also helpful because then you know that you’ve been treated with the drug.

BROOKS KENNY: And that’s probably a really good question for people to ask up front, when they’re considering a trial?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes. Yes, asking, well, is there an open label period where I will get the drug? Because that might influence your decision to participate or not. So yes, I think that’s a really great question.

And just a few more points about this. And please send your questions in. We want this to be an active dialogue and not so much of a talking head. But I wanted to make a few points about a placebo. So most clinical trials involve comparing the drug to the placebo. And why is this? Well, it’s because effects are small. And most drugs– let’s take the approved drugs. They slow the disease by about 30%. Well, 30% is difficult to see. So you need a placebo to make sure that you are seeing some effect of the drug. And you can do that if there’s a placebo.

And then we are all subject to placebo responses. So if you believe you are on therapy, you’re likely to do better. And that’s true of the doctors. And it’s true of the families. And it can be true of the patients. And so we have to control for the placebo responses. And the way we do that is by having a placebo group compared to the active group because both of those groups will have placebo responses. But the response to therapy, hopefully, will be continued over time. So the placebo is very important. And again, it’s essentially the only kind of data that the FDA will accept. And so it’s very important that it be tested in this rigorous way. And then as we said, there was an open label extension in many trials where you absolutely know you’re getting the drug. And then the number of people who get the placebo can vary from trial to trial. So if you’re testing two doses of drug, then you only have a one third chance of being on the placebo. If you’re testing just one dose of the drug, then you have a 50/50 chance of being on placebo.

But I would make one point, which is that if you’re not in the clinical trial, you have zero chance of getting that drug– zero– because you cannot get it outside of the context of the clinical trial. So even a 50% chance is a great increase in the opportunity to participate in the development of a new therapy.

BROOKS KENNY: That’s such a great point. Really appreciate it. Before we go to the next slides, I am going to take a few questions, Dr. Cummings, from the chat. We have a few questions about privacy and people wondering basically how their privacy is protected in a trial. And you touched on insurance. But a follow up-question from someone else on that is, if they are participating in a trial, would that affect their insurance even if that information isn’t shared directly with a company? So can you speak a little bit to the privacy and what people should be thinking about or asking?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes. So in the recent past, nearly all trial data are captured electronically. If you’ve been in a trial or in a trial office, you’ll see that they have a tablet. And they’re clicking away as you give your answers. Or your loved one gives the answers to the trial. And these electronic instruments are completely secure. And so the data go directly to a server that captures it. And that is available to the sponsor, whether that be an academic sponsor or a pharmaceutical company or a biotechnology company sponsor. And the data are contained and isolated within that system. And it’s never shared outside of the system. If it were to be shared– and, of course, we want data sharing. But if it were to be shared, one, you would have to give permission for it. And two, it would be anonymous when it was shared. So even in the circumstance of data sharing, your confidentiality of who you are participating in the trial is still secure.

So there’s a lot of thinking about data security. We know, of course, there are hackers. You’ve all gotten those letters that say somebody with your personal information was hacked. And that is greatly anticipated in the clinical trial data. And every precaution is taken to make sure that your data are secure. And there would be no sharing with any insurance company or even the hospital system itself. If you had a side effect and presented to the emergency room, you would probably say, well, I’m in a clinical trial. And the emergency staff would decide whether or not they would want to break the blind to know whether you were on the active therapy. But there are very few circumstances where that information would become available.

BROOKS KENNY: Got it. And a follow on to that, if somebody is in a trial and they’re regularly getting tests, like cognitive testing or PET scans, does that data become part of their patient record at any point?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yeah, really great question because you’re doing this in a medical system. But no, it does not become part of the medical record if it is being performed in the context of a clinical trial. So those data are owned by the sponsor of the trial. And they are not owned by the medical system.

BROOKS KENNY: Got it.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: So they are secure also.

BROOKS KENNY: And then the last question before we move to enrollment, someone is asking the difference– and I think this is a great question too. Is there a difference between IRBs when you’re talking about a commercial entity compared to a nonprofit or an academic? Is there any difference in terms of the oversights or kind of the guardrails, so to speak, within the IRB?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: None to my knowledge. The IRBs are governed by regulations. They must meet their own standards of approval. And IRBs can and are reviewed by the FDA to make sure that patients are being protected. So could there be some individual variability? Like, one variability that I know occurs is the rapidity with which an IRB reviews and returns an opinion to the investigator. So some IRBs are just really machines. And you might get an answer in 7 or 10 days. And some IRBs are overwhelmed because they just have too much work to do, too many things to review. And it might be a month or even more before you would get a response. So there is some variability that we would love to reduce in terms of IRB turnaround. But in terms of the scrutiny that the IRB gives the protocol, that is dictated. And they must adhere to those standards.

BROOKS KENNY: Got it. Great. Well, that’s super helpful. So we’re going to move into enrolling in trials. We know it can be overwhelming when people are exploring that and trying to understand their eligibility. So I’d love to cue up that slide and have you speak to that.

And in that context– I’m not going to highlight specific individual stories. But we have had a few people ask about the age range. Like, if they’re one year above or below the age range, how firm is that? We’ve had others ask, if I’ve already done one trial, does that make me ineligible for future trials? So if you could kind of weave some of those scenarios in your presentation of eligibility, that would be super helpful.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Well, we have a great audience, Brooks.

BROOKS KENNY: I know. I’m like, whew.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Very insightful. These are

BROOKS KENNY: Very good question, yeah.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: These are the questions that we want. So the trial is designed to provide a firm answer about whether or not the drug that we’re testing is working or not. And so the trial is much narrower than the general population. So there are eligibility criteria. And they usually have to do with, well, how severe is the memory problem? So right now, let’s take the newer drugs that are being tested, like lecanemab or Leqembi and Kisunla. They’re approved only for very mild patients. And so only very mild patients could come into those trials. And if the patient had more severe or less severe memory impairment, then they were excluded.

But that’s a great way to start. You see whether the agent is working in one population. And if the answer is yes, then you can look at a little bit more severe patients and a little bit less severe patients. But you start somewhere where you think the drug is likely to work so that you get an answer.

And I’m just showing you some scans here on the right part of this screen because a lot of diagnostic confidence rests on this kind of scan. So this is an amyloid scan. And in the upper scan, you see all of that red material. That is amyloid in the brain. And in the lower scan, there’s a little bit of red. And that’s just in the deep parts of the brain. And that’s not amyloid. It’s because the blood flow there is very slow. So the bottom scan is negative. And this top scan is positive. And you might have this scan even if the trial is not of an amyloid drug because we base the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease on the presence of amyloid.

So I’m testing a tau drug. But I want to make sure that I’m doing that in patients who have Alzheimer’s disease. So I would do the scan at the baseline to make sure they have Alzheimer’s disease. But then the rest of the information would be about the tau drug that I’m testing. So these are very important for diagnosis.

And then the kind of things that might exclude a patient if they’d had a stroke, when they have an MRI– that would exclude them, if they have uncontrolled medical illnesses, if they’ve had a recent cancer, or if they’ve had a heart attack within the past three years. Those sorts of things are exclusions because we want to make sure that we’re understanding the drug effect in relatively healthy people. And this is so important because it means if the drug is approved, now that drug is going to be used in a much wider population. And we really have to follow the safety in that wider population because the trial is just one step in understanding the drug. And now, Brooks, you asked me a couple of questions. And what were the specific questions?

BROOKS KENNY: Sure, the three that came in, one was related to age. If someone is just a year older or below, is there a chance they could be eligible? If they’ve already participated in an Alzheimer’s trial, are they able to participate in a future? If they’re taking other medications, could that be an exclusion? I’ll start with those.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Great. We’re testing my memory here.

BROOKS KENNY: I know mine too.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: So let’s start age first. Let’s say that the trial says we’re recruiting individuals who are between the ages of 60 and 80. And your spouse is 81. But you would like to have them in the trial. Could they come in? Many trials will allow that if the other criteria for the trial are met. And the way it’s done is you go to the trial site. The trial site says, yeah, we really want you in this trial. So we have to call the medical monitor because we know that in ordinary circumstances, we have an upper age limit. But there is a mechanism in the trial to make exceptions. And that is through the judgment of the medical monitor. So the doctor at the site cannot make that judgment. But that doctor can call the medical monitor. And together, they would decide whether that was an appropriate person or not.

Now, can a person who’s been in a previous trial be in another trial? And that is something we are really trying to understand right now. Because particularly, if someone has been on one of the new drugs, Leqembi or Kisunla, we know that those drugs have profound effects on the biology of Alzheimer’s disease. And if you take a drug like Kisunla, you stop treatment when the amyloid level is very low or when the amyloid has been removed from the brain. So you stop treatment. But the patient is still progressing, though more slowly. So they could be in a trial. But now, this is no longer the original form of Alzheimer’s disease. This is a greatly altered form of Alzheimer’s disease. And we’re not quite sure how to think about this new population that has been created. But for the most part, we’re moving towards allowing those patients in trials because that’s the real world now. Patients have received these drugs. And we still want to make sure that we’re trying to help everybody we can. So there will have to be subanalyses of those populations. They will have to be handled differently in the clinical trial analysis. But increasingly, we’re trying to allow those patients in. So there is an answer specifically to the question, can I participate if I’ve been in a clinical trial? It will vary from trial to trial. Now, we don’t know specifically.

And then there was a third question on drugs that can be exclusionary. And that’s true. If someone was on opiates for pain relief, for example, but the opiate might affect the cognitive testing, then that might be an excluded drug. So each of the drugs that the person is on has to be considered one by one. We try to exclude as few as possible. But there usually are some excluded drugs.

BROOKS KENNY: Got it. So if you have some– I’m just curious. And I’m actually projecting some of my own personal experience because I remember when my family member was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. And we asked the question, can we look into clinical trials? We were told, no, her case is too complicated. She won’t qualify for any. This was eight years ago. But I’m wondering what you might say to people listening how they should approach that conversation. We’re all about knowledge, education, empowerment. And I’m wondering how you would share with our audience, how do they even bring it up? And what are some of the key questions they should be asking when they are inquiring with their provider?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, a really great question. And of course, patients tend to trust their doctors. And so they ask the doctor for his or her opinion about whether or not they should go into a trial. The challenge is that many neurologists, general psychiatrists, general practitioners do not actually know very much about trials and may never have done a trial in the course of their medical training. And so their information and understanding about trials may not be great, may not be very deep. So if you’re interested in trials, the best way is to speak to someone at the trial site. And of course, they want patients to come in. So they’re getting their phone number out there. And you can have a preliminary discussion with the trial coordinator, and he or she will say, oh, well, that is an excluded drug. Or yes, he had cancer just two years ago. And so we’re excluding that group of patients right now. So the best information is from the people who are constructing the trial population. And I would get the doctor’s opinion. You really want that. On the other hand, I wouldn’t stop there. I would call the trial site.

BROOKS KENNY: Fantastic, that’s great advice. Well, the next set of questions we were going to talk through– and I think we were going to pull up a slide around the phases of trials, which you touched on a bit with your Circle of Hope. But I know this has more info. So would love for you to walk us through it.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yeah, thank you for this. Well, I think it’s important for our audience to understand that a trial is just one step in a larger drug development program that starts as a white powder in the laboratory and winds up as a pill for the patient after FDA approval. And that process has many steps.

So I mentioned this in the phase I trial that’s mainly healthy volunteers. Occasionally, it’s patients with Alzheimer’s disease. And you’re trying to find out, well, what are the best doses? And how does the body metabolize this drug? Is it coming out in the urine? And can we measure it in the urine? And can we measure it in the blood? And there’s usually about 100 participants in these trials. So maybe there would be 20 at one dose, 20 at the next dose, and so on. Maybe you would test five doses or four doses in the phase I trial and try to understand what is the limit of the dose that can be advanced to the phase with our patients. And that usually takes about one or two years. And it costs about $79 million to do a complete phase I program.

BROOKS KENNY: And how do people find out about phase I trials?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: You can do it through clinicaltrials.gov. The Alzheimer’s Association, AlzMatch has that information. And if you go to our own website, the alzpipeline.com, you can actually click on your local map. And it’ll tell you what trials are going on in your local area. So there are at least three sources, probably more, to find clinical trials.

BROOKS KENNY: That’s great.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Then our drug goes along to phase II. And these are people who have Alzheimer’s disease to understand whether it’s working on the drug. There’s usually between 120 and 400 people. And there might be one or two doses tested at this level. You’re looking for safety, always looking for safety. Is the drug affecting blood pressure? Is it affecting the blood count? Is it affecting the heart rate? These are all so critical to making sure that our drugs are not producing harm, that we’re just able to look at the benefit. And a phase II program is longer because you have to test the drug for longer periods of time. So it’s usually three or four years to get through a phase II program. And the cost of that is about $140 million. So it’s expensive take now to get to through phase II.

If phase II looks good, then you would go on to phase III. And here, these are large trials. 300 would be very small. We certainly have trials now with 3,000 or more participants. And the trials are large because we need to have confidence in the results. This confirms the efficacy in the safety. So we sometimes think of phase II as learning and phase III as confirming. And that’s, I think, a good way of thinking about the balance of these two types of trials. This is the preparation for the FDA review. So this is the final step before it goes to FDA. They take about three to five years to do a phase III program. And they’re tremendously expensive, $462 million on average for an Alzheimer drug.

So if that succeeds, then you would go to the FDA for approval. But that then starts this more loosely defined phase IV process because we still want to know about the safety of the drug in this less well-defined population. So there is a continuous collection of information even after the drug is accepted. And there may be some specific trials. Let’s say, for example, that we didn’t have very many young patients in the trial, young meaning between 60 and 75. Most of the patients were over 75. Well, you might do a specific trial on younger patients in order to understand whether early onset Alzheimer’s disease is also responding. And that would be a phase IV trial after approval.

And so that’s the spectrum of trials that goes on. And you see that each trial is a step forward. And eventually, we’re trying to get these drugs into the hands of patients. That’s our goal.

BROOKS KENNY: Got it. Fantastic. We have a bunch of questions about potential risks and side effects. And if you could speak a little bit to that, what people should expect, what should they ask their doctor or the trial coordinator when they’re entering a trial.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, this is so important because a drug is in a trial because we don’t have complete understanding of it. We don’t completely understand its efficacy. We’re trying to understand, does it help? But we also don’t completely understand its safety and therefore side effects. Either ones that we anticipate or ones that we don’t anticipate can occur in the trial. And that’s why there’s so much attention to safety in the trials. Patients are asked about their symptoms. There are blood tests. There are urine tests, all sorts of testing, EKGs that are aimed at catching any abnormality that is being produced by the drug.

And sometimes, we know about side effects. And we must discuss that with the patient. So in the antibody therapies, like Kisunla and Leqembi, when they were being developed– and now that they’re in the population, they produce ARIA, Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities, which is the leakage of fluid or the leakage of blood into the brain. Most of them, 75% of those occurrences, have no symptoms associated with them. The patient would never know that they had it if we weren’t routinely monitoring them in the early part of therapy with MRI. But sometimes, they do have symptoms. And that would be important to report to the site. Headache is the most common symptom. But there can be confusion. There can be seizures. There can be weakness on one side of the body or the other.

And so those are all very important. And we monitor for that in the early part of therapy because that’s when this side effect is likely to occur, is in the first months of therapy. So we’re very careful about getting MRIs so that we know if ARIA has occurred. And even if there are no symptoms, we would usually stop the treatment to see whether the abnormality resolves. And if it does, then we could start treatment again. If it does not, then we would say, no, this person should not be on these drugs.

So this is a side effect that we know, that we understand. We understand how to monitor it. But it is very, very important to have this discussion with the trial site because you, the participant, is accepting this risk of a side effect in these trials.

BROOKS KENNY: Got it. So I can’t believe how fast this hour is going. We do have some specific questions, Dr. Cummings, about trials themselves and what might be available. One person has asked, are there any clinical trials that you’re aware of that target both amyloid plaques and tau tangles at the same time? Since it’s been established that amyloid plaques slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s, we want to make sure we get a drug that will– I won’t go into the whole thing. Are there any that combine these two?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yeah. What an informed question. That is great. There’s only one trial that I’m aware of right now that specifically targets both. So it’s being done at Wash University in the DIAN-TU program. So patients are put on an amyloid drug. And then later, a tau drug is added to that. And right now, that is open only to people who have the inherited type of Alzheimer’s disease. So it’s not very widely open. But it’s a pioneering study that is going to inform us about the concomitant use of amyloid and tau drugs.

And then Dr. Boxer at the University of California, San Francisco, is constructing what’s called a platform trial. And platforms can go forward in time testing many drugs. And his idea is to test combinations of anti-amyloid and anti-tau therapies. That trial has not started yet but will be more widely available. And so I would be very careful to follow any news on that trial. And the platform is called the Alzheimer Tau Platform, the ATP.

BROOKS KENNY: Great. Thank you. Someone else asked– they said that they tested positive for the APOE and APOE4 carrier status. What kind of trials should that person look for? I mean, it’s probably like they go to clinicaltrials.gov or to go to your website and probably search in that area, right?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: They absolutely can. And I am disappointed to say that there are very few trials that are specifically targeting the effects of APOE. And I’m disappointed because it is a risk factor, an important risk factor. And we should be paying more attention to these things that we know put patients at risk. But it’s a very hard target. So there are very few trials for people, specifically for people who are E4 carriers.

Now, the E4 carriers can participate in every trial. And the E4 population of that trial is almost always separately analyzed at the end of the trial. So we do understand at the end of the trial, well, did the drug work less well or better in people who were E4 carriers? Either is possible. So it doesn’t exclude one from participating in a trial. But there are very few trials specifically for E4.

BROOKS KENNY: Got it. We had a few people, Dr. Cummings, ask about moderate dementia or Alzheimer’s. And I think they actually acknowledge here that they were turned down for many trials. And I think it’s an interesting place we’re in. There was so much hope around this early– if we can get people therapy early, early, early. But yet, there are still millions of people that are living with the disease. And are there trials for moderate or even more severe folks that are looking at symptoms?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Again, I share your frustration with this because the patient that I would see in my office was often more severely impaired than would be eligible for a trial. And I always was disappointed that I didn’t have more things to offer. So there are series of trials right now that allow patients with more severe disease. But most of them are targeting the psychiatric symptoms that are common in later disease, either agitation or psychosis. And those are very important symptoms. And we really need drugs for them. And I’m excited about some of the drugs that are in the pipeline for this. So there is progress there. But we’re not seeing the use of drugs that slow the disease, that improve the symptoms in more severely affected patients. And we really need those. So I’m hoping that the field will move in that direction.

I think the reason we’re seeing so much work in early disease is because it’s easier to treat a disease when it’s more mild. That’s true of all of the conditions that we have. When it’s more mild, it’s easier to get relief. And so the trials, where they’re trying to understand the drug effect, have focused on these early populations. But we cannot abandon our moderate and severe patients. We have to find new treatments for them. And I just hope that’s in the next step.

BROOKS KENNY: Yeah, I agree. I mean, quality of life and the quality of your years is really important. So I appreciate that. A little bit on the other end of the range, someone wrote in, as a cognitively “normal,” in quotes, individual without any symptoms but a family history wanting to participate in trials, are there opportunities for me?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes. So there are, I think, four phase III prevention trials right now going on. And they are inviting people who are cognitively normal but maybe have a family history. Or maybe they know that they have this E4 risk factor. And then they get a scan or I think now actually a blood test is sufficient. And if that’s positive, then they would be invited into the trial. So there are trials. And next week in Washington, DC, we’re having a day and a half meeting on exactly prevention trials because this is the next step. Let’s make it so that nobody gets Alzheimer’s disease. That’s our goal.

BROOKS KENNY: Absolutely, absolutely. Well, we are starting to wrap up our time. And I would love for you to share with folks what you’re most excited about in the clinical research space in Alzheimer’s disease. Certainly, there’s always going to be challenges. But would love to– building on your two phrases that I wrote down, these citizen soldiers who are engaged in research and your Circle of Hope, we want people to feel certainly empowered to take this information home with them and really understand how they can move on to the next step, whatever that might be for themselves or their loved ones. So what words of hope can you offer?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes. Well, again, thank you for having me today. This was a “bright focus” of my day. And so it’s really great to be here and to talk with people who are really interested in this because it’s immediately important to them. And I can’t thank people enough for both becoming informed and for participating in clinical trials. It is the only way forward.

But there is a lot of progress. For example, we know that we have approved monoclonal antibodies, anti-amyloid. But we are making such progress in improving the safety and efficacy of those drugs already. So what we’re looking back at is the first generation of drugs. And we’re already looking at the next generation of drugs. So there’s going to be progress there.

There are some very exciting tau programs. One of them requires putting the drug into the spinal fluid. But we’re getting better and better at that. And there are many kinds of cancer and other disorders that are treated in exactly that way. So although it sounds complicated, it’s actually something that is very familiar to doctors. So I’m excited about that.

As I mentioned, the drugs for psychosis and agitation are making great progress. I’m excited about that. There’s, I said, 182 trials producing 182 chances for success. So the Circle of Hope is very robust. And I’m just hoping that we’ll see success in many domains in the coming years. And I think we have that opportunity.

BROOKS KENNY: Fantastic. Well, thank you so much. That was a perfect wrap-up. And as our time comes to a close, I just want to thank you again, Dr. Cummings. On behalf of everyone at BrightFocus and our ever-growing community, we’re so grateful not only for your time today but for your life’s work and your commitment to research and to your patients. So thank you for being with us.

I am going to ask our team to show some resource slides now just as we wrap up on how to find a trial we will certainly post those links that Dr. Cummings mentioned in his remarks so that you all have them. We’ll make sure to add yours to that list and send that out in the presentation notes when we follow up with folks.

We also just want to remind everybody about the BrightFocus resources on our next slide. We certainly have a clinical trial finder tool. We have publications. We have a lot of information that you can find on our website. So we encourage you to go there as well.

We will be sending out a recording and transcript of this episode to all of you via email in about a week or so. And we’ll include the resources that we discussed today. You can always check back at brightfocus.org/zoomin to look at any of our past episodes, as I had mentioned.

Looking ahead, we have future episodes coming up. And we will certainly keep you all posted on future topics. But I want to remind you, as we often do, we are here for you. Our mission and our vision is to really put an end to these diseases through research, through advocacy, and through public education.

And so we want to know what matters to you. So we want to hear from you. We want you to write to us and let us know the topics that you’re interested in. So don’t hesitate to keep that conversation going as we go month to month.

And finally, our next Zooms that are coming up in February– we have one on February 20th, The Path Forward in Stopping Alzheimer’s Disease, and then another one in clinical research on April 3rd, which we will be announcing in more detail in the coming weeks. So keep in touch with us. Stay connected to us on social media and on the website. And we look forward to hearing from you between now and our next episode, and then looking forward to seeing you again in a Zoom In on Dementia and Alzheimer’s.

So with that, I thank you. And I hope you enjoy the rest of your afternoon. And thanks again, Dr. Cummings.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Thank you all.

Resources:

Where to find a clinical trial: