Researchers, including BrightFocus grantees, have been examining how modifiable lifestyle interventions such as intermittent fasting, the “fasting-mimicking” diet (FMD), ketone supplementation, and other targeted diet changes can help people delay Alzheimer’s disease, improve cognition, and live longer.

Although fasting—or time-restricted eating within a certain window—has long been explored as a quick weight-loss tool, research into the many other health benefits of fasting techniques has been ongoing for decades. Recent findings on time-restricted eating methods, nutritional changes, and other interventions have shown positive and promising results in animal studies and limited human studies related to Alzheimer’s disease and cognition, although more controlled, randomized human trials are still needed.

But how do these “biohacks” really work? What does the research show, and who could benefit?

How fasting and the ketone factor combat aging

Fasting causes the coordinated alteration of numerous metabolic and transcriptional mechanisms that can influence cells throughout the body, producing an altered metabolic state that optimizes cellular functioning by removing or repairing molecules. This increases resilience to stress, reduces blood glucose, and decreases inflammation—culminating in maintained or enhanced cognitive performance.

A central aspect of fasting–which is different from just restricting calories–is that the body undergoes a metabolic switch from using glucose to using ketones as fuel, entering a fat-burning state called ketosis, a result of the depletion of liver energy stores and the mobilization of fat.

The metabolic changes that occur during repeated cycling from fasting to eating may help to support brain function and resistance to stress and disease.

Ketones trigger the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a molecule that promotes the growth of new brain cells and protects cells from stress, allowing them to live longer and strengthen neurons and neural connections in areas of the brain responsible for learning and memory.

According to neuroscientist and brain aging expert Mark Mattson, PhD, National Institute of Aging (as published in an interview), scientists have discovered that fasting increases ketone levels more than the standard ketogenic, or low-carb “keto” diet. Ketogenic diets can increase ketones fourfold whereas fasting has been shown to increase ketones by up to twentyfold. As a result, fasting, compared to a ketogenic diet, may have a stronger, more beneficial effect on overall health and aging.

An active Alzheimer’s Disease Research project at BrightFocus is also investigating how brains use ketones as fuel against Alzheimer’s. Researchers are developing new imaging probes to visualize how the brain utilizes ketones as an alternate energy source and comparing these signatures to brain glucose metabolism. Highly anticipated results will provide new insights into potential treatment pathways and are expected to be published in the coming months.

It is important to note that mainstream ketogenic diets have been associated with adverse effects such as gastrointestinal problems, weight loss (which often should be avoided in neurodegenerative diseases), high cholesterol, and vitamin and mineral deficiencies. And while no major nutritional modification plan should be undertaken without consulting a doctor, researchers have also found exogenous ketone supplementation with ketone bodies, or ketone-infused drinks, to have similar results to intermittent fasting in some studies.

Further, genetic risk factors may also play a role in the efficacy of these lifestyle interventions, as is also currently being investigated by an Alzheimer’s Disease Research project at BrightFocus.

Eat to live longer

Valter Longo, PhD, author of The Longevity Diet: Discover the New Science Behind Stem Cell Activation and Regeneration to Slow Aging, Fight Disease, and Optimize Weight and a professor of gerontology and biological sciences at the University of Southern California and director of its Longevity Institute, advocates for the practice of a healthy lifestyle that includes dietary and lifestyle interventions such as the longevity diet to promote healthy aging, live longer, and delay Alzheimer’s disease progression. In 2018, TIME Magazine named Dr. Longo as one of the 50 most influential people in health care for his research on fasting-mimicking diets as a way to improve health and prevent disease. Based on two decades of clinical studies and epidemiological research, including research into populations that get less Alzheimer’s diagnoses, such as centenarian-abundant longevity hotspots Okinawa, Japan, and Loma Linda, California, Dr. Longo described the plant-heavy longevity diet as “more of a food-based drug that has most of the benefits of a vegan diet without the problems of a vegan diet,” such as malnourishment and increased stress fractures.

The longevity diet is nearly free of the saturated and trans fats found in high quantities in animal-derived foods, which have been associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in studies conducted at the Chicago Health and Aging project. Processed foods have also been linked to an increased risk of dementia.

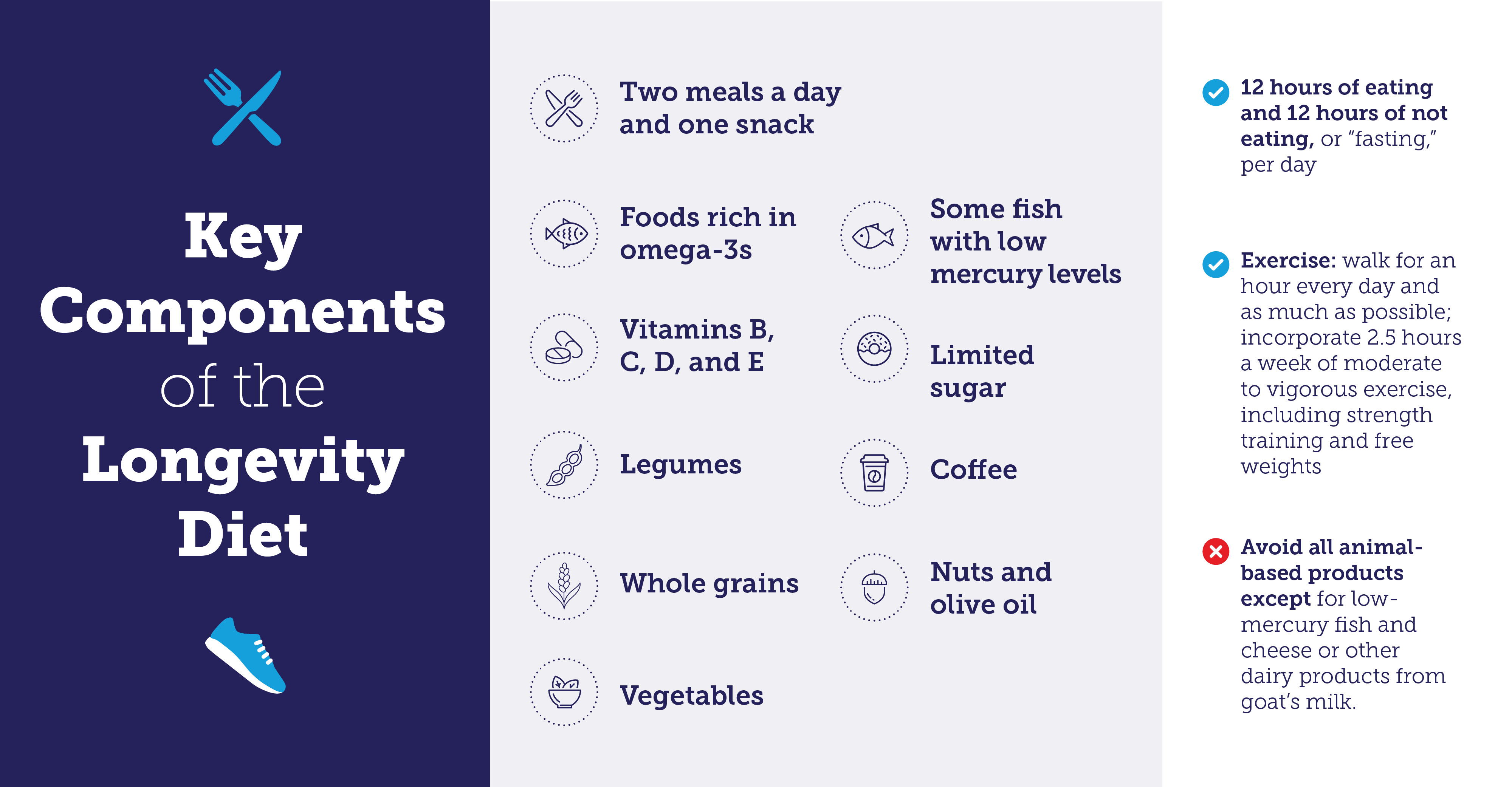

Components central to the higher-complex carb, lower-protein longevity diet include:

- two meals a day and one snack

- foods rich in omega-3s

- vitamins B, C, D, and E

- legumes

- whole grains

- vegetables

- some fish (with low mercury levels)

- limited sugar

- coffee – olive oil (3 tablespoons per day) and nuts (1 ounce per day)

- avoid all animal-based products except for low-mercury fish and cheese or other dairy products from goat’s milk

- 12 hours of eating and 12 hours of not eating, or “fasting,” per day

- Exercise: walk for an hour every day and as much as possible (take the stairs if you can); incorporate 2.5 hours a week of moderate to vigorous exercise, including strength training and free weights

In a study published earlier this year in the journal Cell, Dr. Longo and coauthor Rozalyn Anderson of the University of Wisconsin said that maintaining a BMI lower than 25, along with ideal sex- and age-specific body fat and lean body mass levels and abdominal circumference, should be used as guidelines to establish daily food intake rather than a set calorie level. In younger and middle-aged adults, a high BMI is associated with reduced cognition or a higher risk of dementia later in life.

Evidence is also growing to support the notion that intermittent fasting can have health benefits associated with cardiovascular disease, mood, and diabetes—a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease—among others. Those who have diabetes can only fast under strict health and medication monitoring as it is not a practice that is suitable for every individual and may also be harmful if you need food at certain times or take medication that affects your blood.

The “fasting-mimicking” diet

In a recent study in Cell Reports, investigators including Dr. Longo discovered that cycles of a diet that mimics fasting appear to reduce signs of Alzheimer’s in mice.

The “fasting-mimicking” diet, which is also a pillar of the longevity diet, is designed to mimic the effects of a water-only fast while still providing necessary nutrients. In mice, researchers found reduced brain inflammation and increased cognitive performance in addition to lower levels of two disease makers: amyloid beta—the primary component of plaque buildup in the brain—and hyperphosphorylated tau protein, which forms tangles in the brain.

Early clinical data indicates that five days a month of the FMD are safe and feasible for the group of patients with mild impairment or early Alzheimer’s disease who were also studied; however, Dr. Longo stated that further human studies are still needed and that individuals should not undertake this regimen without close supervision by medical professionals. Notably, the clinical trial also provided patients with daily supplements of plant-based fats to promote a more ketogenic state.

So, should everyone just start fasting?

It’s not that simple. Every person is different, and only a doctor or qualified medical professional should provide guidance on what is appropriate.

People who need to take certain medications that require food or who take heart or blood pressure medications may be more likely to suffer dangerous imbalances in potassium and sodium when they’re fasting. Those who have a history of disordered eating are not advised to try intermittent fasting, which can also bring about a host of side effects, including fatigue, insomnia, nausea, and dizziness.

In a review of the research by the National Institute of Aging published in the New England Journal of Medicine, authors Rafael de Cabo, PhD, of NIA’s Intramural Research Program (IRP), and Mark Mattson, PhD, stated that while the benefits of fasting are evident, human trials have mainly involved relatively short-term interventions and have not provided evidence of long-term health effects, including effects on lifespan, and that studies are needed to determine whether this eating pattern is safe for people at a healthy weight, or who are younger or older, since most clinical research so far has been conducted on overweight and middle-aged adults. In addition, research is needed to identify safe, effective medications that mimic the effects of intermittent fasting without the need to substantially change eating habits.

The bottom line

Ultimately, “biohacks” like fasting or time-restricted eating are just words that have limited value; one size does not fit all. What is more important is what type of fasting or time-restricted eating method is best for an individual, if any, and additional Alzheimer’s disease research is still needed in humans.

The good news?

It’s never too late to start incorporating healthier nutrition practices tailored to individual needs in partnership with medical professionals in the quest for improved cognition.

Making healthy diet changes through programs such as the longevity diet or other plant-friendly, clean eating practices is a more accessible and proven way to boost cognition through a diet rich in vegetables, complex carbohydrates, and omega-3 fatty acids and low in added sugars and unhealthy fats.

Dr. Longo encourages anyone whose parents or grandparents had Alzheimer’s disease to pursue genetic testing and determine if they have risk factors for the disease and to talk to their doctor about diet modifications that can help prevent or delay the disease. Researchers have also linked several other eating patterns—such as the Mediterranean diet, DASH diet, and MIND diet—to reduced Alzheimer’s risk, providing more options for individuals looking to cultivate brain health through their diet.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Brain Health

- Diet & Nutrition

- Lifestyle

- Nutrition