A Dutch study of people over age 100 reported that despite having amyloid beta present in their brains, many centenarians maintained sharp minds throughout their lives – a finding that raises new questions about the role of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease.

The research team, led by BrightFocus grantee Henne Holstege, PhD, of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, concluded that amyloid may not play as big a role in dementia as previously believed. Rather, it is two other proteins—tau and TDP-43—that may be responsible for cognitive decline.

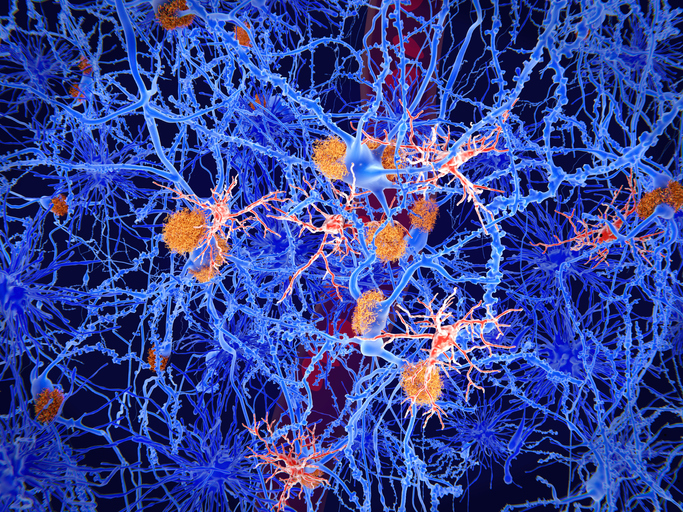

Changes in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s disease include the formation of amyloid beta plaques and tau tangles. However, other toxic proteins like TDP-43 present as co-morbidities during later stages. Many of the centenarians in the study had significant accumulation of amyloid in their brains but were not cognitively impaired. Once tau or TDP-43 built up, however, cognitive decline was accelerated.

“Our data suggest that the deposition of amyloid beta plaques may be a natural consequence of aging and not directly causative of functional decline in centenarians,” the researchers wrote. They noted that a significant amount of amyloid deposits observed in the centenarians investigated in the study consisted of a less toxic form of amyloid.

About the study

The “100-Plus Study” enrolled 330 healthy people ages 100 and over who had high levels of brain function at the start of the research. Of those, 85 people agreed to donate their brains after death for study. The age at death of the brain donors ranged between 100 and 111 years.

Trained researchers visited the centenarians at their homes once a year to perform comprehensive cognitive tests, such as assessing their memory, verbal skills, attention, how well they process information, and other measures of brain function.

They found that some centenarians maintained the highest levels of cognitive performance despite having amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles found in their brains after death, which are considered hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

The researchers speculated that centenarians may be resistant to a buildup of amyloid, possibly because their brains were healthier later in life. Another theory is that centenarians may have developed ways to compensate for these neuropathological brain changes.

What’s next

The findings from this study suggest that a decrease in memory and brain function is not an inevitable part of aging. The next step for the researchers is to learn more about the role of tau and TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s.

“To increase our understanding of the association between neuropathological burden and cognitive performance, we propose that future studies address the loads and subtypes, rather than distribution, of neuropathological (factors),” the researchers wrote. They plan to examine how these factors correlate with cognitive ability in later years.