All Your Questions Answered About Macular Degeneration

Featuring

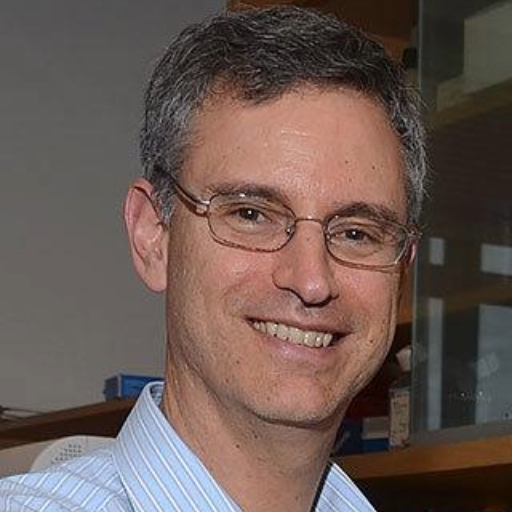

Joshua Dunaief, MD, PhD

University of Pennsylvania

Joshua Dunaief, MD, PhD

University of Pennsylvania

Guest speaker Joshua Dunaief, MD, PhD, answers your questions about macular degeneration. Dr. Dunaief is a professor of ophthalmology at the Scheie Eye Institute of University of Pennsylvania. He has cared for patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) since 2000, and his lab focuses on developing new understanding and treatment of AMD.

Download English Transcript PDF Download Spanish Transcript PDF

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Hello. My name is Diana Campbell, and I am pleased to be here with you for today’s macular degeneration Chat, “All Your Questions Answered About Age-Related Macular Degeneration.” I’ll refer—and our speaker will also refer—to both macular degeneration and AMD. I just wanted to make that clear for everybody. For those of you who are new to our Chat series, this Chat is brought to you today by BrightFocus Foundation. We fund some of the top scientists in the world who are working to find better treatments and ultimately cures for macular degeneration, glaucoma, and Alzheimer’s disease. And we do events like today’s Chat to get the latest news from science as quickly as possible to families that are impacted by these diseases. You can find much more information on our website, www.BrightFocus.org. Now, I’m pleased to introduce today’s guest, Dr. Joshua Dunaief. Dr. Dunaief is a professor of ophthalmology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He cared for patients with macular degeneration from 2000 to 2018, when he decided to devote his time to macular degeneration research. Dr. Dunaief serves as the vice chair of research for his department and chair of an NIH grant review study section. He has actively kept up with all the clinical developments. Josh, thanks so much for joining us today.

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Thank you, Diana. Good to be with you and to be able to reach so many patients and their families and friends with the latest information.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: We’ve got a lot of great questions coming up, so let’s dig right in. First of all, we’ve gotten a lot of questions about this. We had some really exciting news last month. Syfovre, the first-ever treatment for geographic atrophy, was approved by the FDA. We also get a lot of questions about geographic atrophy itself. So, let’s start with the basics of geographic atrophy, or GA. Can you walk us through the progression from dry AMD to geographic atrophy and what constitutes a diagnosis?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Sure. So, macular degeneration is very rare among people younger than 55 but quite common as people get older than 55. Up to 20% of the population will have some form of AMD over the age of 80. And the first sign of it is actually asymptomatic. It’s something that can be detected by an ophthalmologist or an optometrist when they look into the eye through the pupil. And what they see in somebody with early macular degeneration are these little white dots under the retina. They’re called drusen. That’s a German word that means pebble, so it’s as if they had little pebbles under the retina. And again, this is usually asymptomatic. It’s just an indication that patients with drusen are at an increased risk of losing vision at some point in the future, which is not to say that everybody with drusen is definitely going to lose vision in the future; it’s just an increased risk. And the risk is determined by the number of drusen, the size of drusen, and some other things about the appearance of the retina that we can go into a little bit later.

Now, some people will progress from just having drusen to having something called geographic atrophy, and geographic atrophy is kind of what it sounds like. It’s a patch—kind of like a continent—think like Australia … a patch in the shape of Australia—where the retinal cells that sense light have died. And this patch will expand over time. Once it starts, it will expand, and the patch causes a blind spot because the cells in the retina that sense light have died and, therefore, that area of retina can no longer sense the light. So, people with a little patch of geographic atrophy might be looking at somebody’s face and notice that part of their nose is missing or that one of their eyes is missing. Or they might be trying to read and notice that a few of the words or letters on the page are missing. Or they might be looking at something that we call an Amsler grid, which is a graph that we give out to patients, and we recommend that patients look at that graph, closing one eye at a time actually, because if one eye has geographic atrophy and the other doesn’t, the good eye will substitute the image and you won’t notice that there’s a problem. So, using one eye at a time, look at this graph and see if you can see all the lines. You look right at the central dot and make sure you can see all the lines on the graph. If some of them are missing, that could be a sign of some geographic atrophy.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Thank you for that description. So, as that continent grows, at some point then you’re diagnosed or you’ve progressed to geographic atrophy rather than just having dry AMD. So, given that description and that background, how does Syfovre, the medication that was just approved, work in the eye?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Yeah. So, Syfovre is the first drug that’s FDA approved now for geographic atrophy. What it does is to slow down the rate of growth of that patch of atrophy, or that continent. It doesn’t restore vision that was already lost. It doesn’t shrink the size of that blind spot, unfortunately, but it just slows down the rate of growth of the blind spot by as much as somewhere between 25 to 36%, depending on what period of the clinical trials you look at. The clinical trials were done in many patients. Over 12,000 injections were done in the clinical trials, and these patients tended to do the best in the later parts of the trial. They were followed over 2 years, and they were given an injection every month of this drug into the eye for 2 years. And the slowing of the geographic atrophy expansion seemed to be most pronounced towards the end of the study, which suggests that it could be the longer patients stay on this drug, the better they’ll do.

Now, an injection into the eye sounds like really an awful thing, and I have had to sit down with my patients and really explain what it’s going to be like before they undertake one of these, understandably. Fortunately, we can numb the eye with eye drops and by holding a little Q-tip on the eye soaked with numbing medicine, and then clean the eye very carefully, and then inject the medicine right into the center of the eye through a needle that’s tiny, like the width of a hair. And it only takes a few seconds. It’s a little uncomfortable, but most people think that it’s nowhere near as bad as they initially felt it would be. So, this drug does slow the rate of growth of the atrophy, thereby over time protecting some of that vision that could have been lost if the atrophy had spread as it normally would without treatment.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Great, and definitely better than the other alternative of continuing to lose vision, as well. What suggestions do you have for people who are interested in Syfovre or may even wonder if they have GA? What are the types of questions that they should be asking their doctor?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Well, that’s a good question in and of itself. So, they should ask their doctor if the doctor thinks they’re a good candidate for Syfovre. Some patients may not think that the 20 to 35% slowing rate is worth getting injections in the eye every month to prevent. It is a time commitment for the patient and for whoever is bringing the patient to the office every month. It is a little bit uncomfortable to get the injection. And there are some risks—not real bad—but there are some risks. The most common complication is something called wet macular degeneration, which is where new blood vessels grow into the retina and leak and bleed and cause some damage. This happens in about 2% of patients who aren’t treated with Syfovre, about 7% of patients who are treated every other month, and 12% of patients who are treated every month. So, the injections do increase the risk of wet macular degeneration. Now, wet macular degeneration can be treated with, kind of ironically, another injection of a different drug that blocks a protein called VEGF. VEGF promotes blood vessel growth, and these treatments block VEGF. So, patients who start to develop wet macular degeneration could get both Syfovre and anti-VEGF injections to keep the wet macular degeneration in check while also slowing the progression of the geographic atrophy.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Great. I know there are a couple of other trials ongoing that will have results kind of on the heels of the Syfovre approval. There’s Zimura. We’ve also had a question about the Ionis trial for geographic atrophy. What ongoing trials look promising to you, both for dry AMD or geographic atrophy, as well as wet AMD?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: So, the next drug that is likely to be approved for geographic atrophy is Zimura, as you mentioned. Zimura actually targets a different target but in the same pathway as Syfovre. Syfovre targets a protein called complement, which is a component of the immune system. It’s been shown over the past decade or more that the complement cascade—again, part of the immune system—promotes macular degeneration. And that was shown through genetic evidence and also by looking at eyes that were donated after death from people who had macular degeneration and seeing that complement is actually activated in these eyes.

So, for over a decade, researchers thought that probably targeting complement would be helpful for patients with macular degeneration. These trials from Zimura and Syfovre are evidence that this is correct, that blocking this inflammatory complement cascade does help; it does slow the expansion of geographic atrophy. So, Zimura targets a different complement protein—it’s called C5—while Syfovre targets its upstream partner, called C3. And in the trials, the results seem pretty similar between Zimura and Syfovre—the benefits seem about the same, the side effects seem about the same—but probably Zimura is going to get approved, too. You’ll probably ask me next which one I think is going to be better, and I won’t be able to tell you that because they haven’t been compared in a trial head to head, so it’s hard to say, but they both do seem to work.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: That’s really exciting that there will be options.

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Oh, yeah. It sure does. And the Ionis trial also is targeting a complement component—so, the same pathway but yet another complement protein in that pathway. So, that one could potentially work, as well. We’ll have to see how the clinical trials pan out. If we look at the wet macular degeneration world, probably what we’re going to see is kind of a competition among these drugs to see which one needs to be injected the least frequently and still have a good effect because patients are always asking, “Do I really need to get an injection every month? Could I come every other month or even less frequently?” And in the case of wet macular degeneration, fortunately we have had anti-VEGF drugs that have been developed that last longer than the original.

The original FDA-approved drug was Lucentis, and that one works best when it’s given once every 4 weeks, but there are other drugs now. There’s Avastin, which lasts about the same amount of time as Lucentis, and then there’s Eylea, which lasts a little bit longer than Lucentis, so that one was the most popular for a while. And then now there’s another one that has just come out fairly recently, and that one lasts even longer. It’s called Vabysmo. And that one is a little different because it targets not only VEGF, but also another protein that promotes blood vessel growth called ANG2—ANG2. So, again, I think we’re going to be seeing the same thing with the anti-complement drugs. We’ll be seeing them lasting longer and longer so patients won’t need to get these injections so frequently. And we may even be seeing some gene therapy where it’ll be a one and done—just one shot where the gene therapy lasts for years and keeps the macular degeneration at bay.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: There’s a lot on the horizon. That’s really exciting.

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: It sure is.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: We’ve gotten a handful of questions from Anna, Catherine, and Mary about the potential for stem cells to grow new retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells or to be used in therapy. What can you share about research in this area?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Stem cells are an exciting area. What are stem cells, first of all? They are cells that have the potential to turn into lots of different cell types. So, you can take stem cells and coach them to turn into retina cells and then implant them into the retina. And stem cells can actually be made from skin cells or blood cells and then coached to turn into eye cells. Amazing technology. And these can be grown on sheaths of biodegradable material, rolled up, unfolded under the retina, and then left there to take up residence. And they do survive for at least a year that human clinical trials show. It’s not yet clear whether these are going to restore vision. There are some very small trials suggesting that they might, but I think so far that the clinical trials are looking pretty optimistic for this. One word of caution for patients: Please don’t get any type of stem cell therapy outside of a clinical trial. There are some practitioners who will give risky stem cell treatments that are not sanctioned through clinical trials known to us. A few people have gone blind as a result of that, so be aware of that.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Thank you for that very important caveat. I’m really, really glad you mentioned that. Another hot topic, it seems, in terms of the questions we received this month, is about zebrafish: What makes zebrafish so interesting in studying AMD, and what hope might they provide?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: That’s a fantastic question. Zebrafish eyes are special because when the vision cells die, they regenerate. And that is, unfortunately, not something that our eyes can do, and most other animals can’t do that, but zebrafish can. So researchers are looking at zebrafish eyes to understand how they can do this, and what they’ve discovered is that there’s a type of support cell that’s normally in all retinas—it’s called the glial cell—and these glial cells can turn into light-sensitive photoreceptors when the photoreceptors have died. Our glial cells can’t do that, so researchers are looking at differences between zebrafish glial cells and our glial cells to see if we can figure out how to get our glial cells to turn into photoreceptors when the photoreceptors have died. There’s actually a researcher here at the University of Pennsylvania Scheie Eye Institute. She’s sitting about 1,000 feet from me right now on the other side of the floor, and her name is Dr. Katherine Uyhazi, and she’s one of the people who’s very actively engaged in understanding these differences between zebrafish and human glial cells and trying to convince them to become photoreceptors or transplant photoreceptors to replace photoreceptors that have died in patients with macular degeneration and other retinal diseases.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: So, in this case, it sounds like they would help to restore vision rather than stop progression or slow progression. Is that accurate?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: It is, yeah. Everything else that we’ve been talking about up until now is designed mainly to prevent further vision loss. There isn’t much recovery of lost vision from … well, not from the anti-complement therapies for geographic atrophy. The anti-VEGF therapies for wet macular degeneration actually can bring back some vision that was lost because they reduce the amount of blood vessel leakage and swelling in the retina, and then sometimes patients will experience an improvement in their vision after anti-VEGF drugs have dried up the retina. But transplanting lost vision cells in a way that patients with, for example, geographic atrophy might be able to regain some vision that they’ve lost because of an area of atrophic, dead vision cells.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: How exciting is that? I’ll ask one last question about potential new treatments and clinical trials before we switch gears. We received a few questions about people traveling to Europe to access Valeda and another about the LIGHTSITE trial here in the U.S. How does this treatment work, and when might it be available in the U.S.?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Yeah, this is an interesting thing. It’s a device—Valeda—made by a company called LumiThera. It’s a device that shines a light into the eye that is thought to be helpful for patients with macular degeneration. It uses something called photobiomodulation, which is where specific wavelengths of light are thought to be beneficial because they can be absorbed by proteins in the mitochondria, the power center of the cell, and help them to function more efficiently. And there is evidence of problems with mitochondrial function in AMD, so it’s plausible that this type of treatment could be beneficial. And the way it works is patients go into this machine and they get exposure to certain wavelengths of light for about 5 minutes, and they get nine treatments over the course of a month. And in a clinical trial, they then waited 6 months and they got another nine treatments, and their visual acuity was followed over time. In a Phase 3 trial, actually, the patients did pretty well. They gained, on the whole, about a line of visual acuity—you know a line on the eye chart—on average.

And also, the risk of going from just drusen to geographic atrophy was reduced in this trial. Now, there weren’t that many patients who got geographic atrophy, so that’s not a really definitive finding, but the improvement of visual acuity by a line is encouraging. The light that you get exposed to is brighter than room light but less intense than looking at the sun, and I think it should be safe, this light intensity, in fairly short duration. So, I would say this is looking promising based on the clinical trials. It’s not entirely proven that it’s effective and not … probably safe. But I think we need to see a little bit more data from this over time to be sure. Now, it is available in Europe, as you mentioned. It is not yet approved by the FDA, and I’m guessing they’re looking at it now because the clinical trials have been done. And I don’t know if or when they might approve it, but it’s an interesting option.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Yeah, a very different approach and angle. We’ll definitely keep track of its pass through to potential approval or not. I’m going to switch gears to folks with questions either about diagnosis, progression, and otherwise managing macular degeneration. We have JoAnn, who was just diagnosed with wet AMD and is wondering how well the injections will stop it from progressing and is nervous about what her future might hold. What can you say about that?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: So, fortunately these injections exist now. Back when I started seeing patients in the year 2000, they didn’t, and there really wasn’t much we could do. Patients diagnosed with wet AMD would almost always lose a lot of vision. But these anti-VEGF drugs are good at helping people maintain their vision and sometimes gain a little bit of vision. But patients really have to keep up with their visits at the frequency that the doctor recommends in order to get the maximum benefits from it and try to maintain their reading and hopefully driving vision. As I said, it’s not easy for people to come to get these injections once a month, or in some cases every other month. Things happen, life happens, and you can’t always get there, and then you might have leaking … bleeding blood vessels for a while that cause some permanent damage during that interval. So, I’d say things are looking much better than they would have in the year 2000. JoAnn, if you keep up with the injections as recommended by your ophthalmologist, you have a good chance of keeping pretty good vision in that eye.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: That’s great advice. How about the progression of dry AMD? People are wondering how quickly it progresses, and if you have it in only one eye so far, how likely is it that the other eye will be affected?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Most patients who have drusen in one eye will have it in both eyes. It’s very unusual to have it in only one eye. That’s what we call early macular degeneration. Patients with just drusen can keep good vision for their whole life with no treatments if they never progress to either wet macular degeneration or geographic atrophy, or some patients even get both in the same eye or wet macular degeneration in one eye and geographic atrophy in the other. The risk of progression from drusen to geographic atrophy or wet AMD depends on a number of risk factors. So, the risk factors are the number of drusen—more drusen is higher risk; the size of the drusen, so larger drusen are a higher risk; also, there can be little spots of pigmentation in the retina that are a risk indicator; and actually, high blood pressure is an additional risk factor. So, depending on the number of risk factors, a patient might have anywhere from a 10 percent chance of developing geographic atrophy or wet AMD over the next 5 years, or if they already have geographic atrophy or wet AMD in one eye, the risk would be about 50 percent for the other eye over the next 5 years. So, an ophthalmologist can look in a patient’s eye and really give them a pretty good estimate of what their risk is going to be over the next 5 years.

But there are things that patients can do once they’re diagnosed with drusen to reduce the risk. So, those things include stopping smoking. Smoking is very much a risk factor, so stopping it is certainly going to be helpful. And then also eating a diet that is healthy, and what do I mean by that, by a healthy diet? The epidemiology says that people who eat a plant-rich diet—lots of green leafy vegetables in particular, and fruit—and some fatty fish twice a week was associated with lower risk. And by fatty fish, I mean salmon, sardines, tuna, mackerel. It’s thought that the oils in the fish may be protective. Although, that prompted researchers to see if fish oil supplements might be protective, and they’re not, so you have to eat the fish, not just the fish oil supplements.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: That’s a really important thing to note. Two quick follow-ups to that. One person just asked: How will I know I’m at the wet stage? So, if they have drusen in both, how will they know they’re progressing to wet AMD, and how often should they be checking in with their eye doctor to watch for that?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Good question. So, the best way for a patient at home to know if they’re developing wet AMD is to cover one eye at a time and look at this Amsler grid with their reading glasses on and with one eye covered at a time. And look at the central dot, and if you see missing, wavy, or a distorted line, that can be an indication of wet AMD. Now, you need to kind of establish a baseline for yourself. Patients may have already some missing or wavy lines, and if the ophthalmologist says, “Oh, you don’t have wet AMD right now,” well that’s your baseline. And then if you notice something that changes from that, that can signal that you’ve developed wet AMD. It may become more obvious, like you could read with that eye one day and the next day you can’t, but sometimes it’s more subtle. The ophthalmologist has a great tool for detecting wet AMD that’s called optical coherence tomography (OCT). This is a type of camera that gives a cross-section view of the retina within a few seconds and shows whether new blood vessels have leaked fluid into the retina. And that’s also a really good way to follow the effectiveness of these injections for wet AMD that block VEGF, because the amount of leaky fluid in the retina will be reduced on these images if the treatment is working.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Great. This next question—you kind of already answered part of it—but this comes from Deborah, and she’s asking: Aside from AREDS vitamins, are there other complementary approaches that could be helpful? You covered diet. She mentioned acupuncture, vascular improvements, and then we’ve had a few questions about other types of supplements.

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Yeah, so AREDS vitamins were shown to be protective. AREDS stands for Age-Related Eye Disease Study, which was an NIH-funded study done over a few years. They took people who had drusen and randomized them to either receive AREDS antioxidants or placebo and then followed them to see who developed advanced macular degeneration—either wet AMD or geographic atrophy. The AREDS vitamins reduced the risk of progression to advanced AMD by 25 percent in patients who started out at a fairly high risk of progression based on the number and size of drusen. So, ophthalmologists or optometrists might recommend the AREDS vitamins if a patient has enough drusen and they’re large enough to qualify as being at significant risk for progression of the disease.

The AREDS vitamins contain lutein and zeaxanthin, which are carotenoids related to beta-carotene, but also contain vitamin C, vitamin E, and the minerals zinc and copper. And these didn’t cause problems in the study patients who took them, so they’re considered safe, at least over the course of 10 years to take the AREDS vitamins. I will offer a warning that there are many types of eye vitamins that are sold over the counter, and the only formula that was proven to be helpful is AREDS, so you need to look at the bottle and make sure it says AREDS—actually, AREDS2 formula because it was refined in a second study. So, look for AREDS2 formula, and the brand that I prefer is called PreserVision, like preserves your vision. I have no commercial relationship with Bausch + Lomb, which makes PreserVision, but the National Eye Institute did test the ingredients in lot of different eye vitamins and found that Bausch + Lomb PreserVision really contains what’s on the label, whereas some of the others did not. You probably know that the vitamin industry is not well regulated, so some of the vitamins that you can buy in the drug store really don’t contain what’s on the label. So, again, Bausch + Lomb PreserVision, is the AREDS2 formula that I recommend.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Great. I think that’s a really important thing to mention, as well. We only have a little bit of time left. Let’s shift over to cataracts. We received various questions about cataracts and how they might impact AMD or vice versa. Are there considerations to make when considering having a cataract removed? And the next question is: Can surgery cause the onset of wet AMD?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Good questions. So, the first issue is that both AMD and cataracts can cause reduced vision, so an ophthalmologist has to figure out for the patient with reduced vision: Is it being caused by the AMD, by the cataracts, or both? And there are ways that the ophthalmologist can figure that out in the office. If the ophthalmologist recommends having the cataract removed to improve the vision, studies have shown that does not increase the risk of AMD progression. So, that’s okay. The surgery does not cause the onset of wet AMD. One thing to watch out for is if somebody already has wet AMD and they’re getting injections for the wet AMD and they need to have their cataract out, then the ophthalmologist will figure out the best timing for the injections relative to the cataract surgery. That’s an important thing to keep in mind, but yes, it is okay to have cataract surgery, in general, for patients with AMD. It’s not typically going to make the AMD worse.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: That’s great to know. That’s very reassuring. Well, we’ve kind of run out of time at this point for questions. To all the people listening today, I sincerely hope you found today’s Chat helpful. Our next chat will be on Wednesday, April 26, and we will be discussing managing wet AMD—basics and treatment. That leaves us with any final remarks you have, Dr. Dunaief. Are there any last tips you’d like to share with the listeners today?

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: Thanks, Diana, for the opportunity to share this information, and I want to thank BrightFocus Foundation for this patient education and also for funding the promising research for AMD to develop the next line of treatments that will be even better than what we have now.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Thank you so much, and we really appreciate your partnership in informing both the listeners today but also everybody online with the expert articles that you do and all the other things we’ve done together. So, thank you, as well.

DR. JOSHUA DUNAIEF: My pleasure.

MS. DIANA CAMPBELL: Okay. With that, this will conclude the BrightFocus macular Chat. Thanks so much for joining us today.

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Through its flagship research programs — Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research— the Foundation has awarded nearly $300 million in groundbreaking research funding over the past 51 years and shares the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

Join us for a conversation about light therapy and macular degeneration, where we’ll explore how different types of light—blue, red, and sunlight—affect the retina, the science behind light therapy, and the newly approved Valeda red light therapy

Learn about how to navigate treatment options, engage in shared decision-making with your healthcare team, and maximize your eye health.

Join us for an in-depth discussion on the latest developments in wet age-related macular degeneration treatment.

Learn about practical tips for maintaining quality of life with low vision.