Learn helpful tips that may delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease or reduce the speed of its destructive course.

In my Memory Disorders Clinic, colleagues and I evaluate many older adults who are struggling with the symptoms of forgetfulness or other cognitive problems. Often patients show up for an appointment with one or more of their children, and I always think of this as a special opportunity. I like to meet the caregivers and to learn more from them about my patients’ lives outside of the doctor’s office. I also want to make sure that caregivers have the information they need to do their jobs.

I answer lots of questions about how to be a caregiver, and frequently need to reply to another burning question from them: “What can I do to prevent this from happening to me?” Since the brain changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease begin more than a decade before the cognitive changes, it seems likely that steps taken early on might alter the disease’s later course.

Steps You Can Take

We can’t change some of the important risk factors such as age or our genes, but other important risks can be modified by our behavior. A great deal of research has already gone into figuring out the most important preventive steps to take, and much more will be done in the future.

Many researchers are participating in this exciting work aimed at preventing or slowing Alzheimer’s through modifiable lifestyle factors. And now, in a recent review article published by Dr. Baumgart and his colleagues, we have a snapshot of current opinion and evidence regarding preventive measures that we all can take, which are summarized below:

Smoking

Smoking is a clear risk factor for cognitive decline in later years, and this risk can be substantially reduced simply by quitting smoking. There is little excuse, in light of current medical knowledge, for beginning or continuing to smoke.

Alcohol

Although a moderate level of alcohol consumption is a recognized component of the healthy Mediterranean and MIND diet plans, too much is now recognized as brain-unhealthy. A recent World Health Organization review of data reached the opinion that alcohol consumption should not exceed 21 units per week. Older individuals and females may do well with an even lower level of consumption.

Diabetes

Diabetes, a disease that affects more than a quarter of older adults in the United States, seems likely to play a role in bringing on early cognitive decline. The relationship between diabetes and dementia is a complicated one because diabetes affects many aspects of health. Management of weight and diet earlier in life can help reduce the risk for diabetes.

Weight Management

Obesity, a widespread problem especially in more affluent countries, is another suspected risk factor for dementia, although not all researchers have reached this conclusion. Obesity in late life, for example, does not seem to be a dementia risk factor.

Cholesterol

Another question that remains open is whether or not high cholesterol increases dementia risk or whether statins decrease dementia risk, though there are other health benefits associated with statin use and cholesterol reduction.

Blood Pressure

Many studies, but not all, have linked mid-life (but not clearly late-life) hypertension with cognitive decline. Medications that reduce high blood pressure in mid-life appear to lower the later risk for cognitive decline.

Physical Activity

Beyond managing medical diseases, very strong support has been given by some studies to the importance of physical activity in reducing cognitive decline and dementia.

Currently, a major topic for scientists is determining more specifically which types of exercise programs are better than others, as well as the best cognitive tests to measure this.

Influential studies have shown that even mild physical activity decreased the risk of cognitive impairment in later life. The exercise was shown to be most valuable if regular and vigorous. Recent research suggests that sedentary behavior during young adulthood such as watching at least four hours of TV daily was linked with poorer memory and executive function in mid-life.

Hearing Loss

Sensory deprivation is harmful to cognitive health, and hearing loss has recently been correlated with increased risk for cognitive decline. Correction of hearing loss is an important step in optimizing cognitive health.

Exercising Your Brain

Cognitive activity, such as more mentally engaging activities like puzzle solving and other brain games, may also be beneficial, though the data are less conclusive about a more specific link to dementia. Years of formal education, a measurement that may be related to cognitive activity, is a strongly supported preventive factor for dementia.

Diet

The effect of diet on optimal cognitive aging has been difficult to study, but reduced risk has been found in studies of the Mediterranean Diet, the DASH Diet, and the more recent MIND diet. Each of these emphasizes limiting red meat and focusing on whole grains, fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, and olive oil. The regular consumption of a small or moderate amount of alcohol seems to help, too, though perhaps not for those who have inherited the ApoE4 gene.

Drinking a moderate daily amount of coffee, in a recent study reported by Dr. Margaret Chute and colleagues, was associated with better memory performance on several tests administered to clinically normal older adults.

Omega-3 fatty acids may have a preventive role for cognitive decline, though a dementia-preventing effect was not found in a large, well-designed study.

Vitamin E supplementation was not found better than placebo for preventing progression from mild cognitive impairment in a well-designed study. Adhering to one of the heart healthy diets appears more beneficial than focusing too heavily on any specific supplement.

Loneliness

Research links loneliness with faster cognitive decline. Previous research, too, has linked the damaging effects of social isolation on health, and supports healing effects of social engagement.

Other Medical Conditions

The risk of cognitive decline is influenced by a number of other medical conditions, and several important treatable ones are depression, sleep disturbances such as apnea, and traumatic brain injury. A recent analysis of many studies also noted the importance of plaque buildup in the carotid artery, excessively low diastolic blood pressure, and abnormally high levels of an amino acid called homocysteine in the blood as risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease.

Spread the Word—Promote Healthier Aging

At present, over five million older adults in the United States and an estimated 47 million in the world live with dementia. Even if a blockbuster medical treatment emerges soon, potentially preventive measures such as those described here should be firmly supported. Anything that delays the onset of cognitive decline or reduces the speed of its destructive course will improve many, many lives. New immunotherapies such as solanezumab and others may help us slow the course of Alzheimer’s disease, but there is no need to wait until these medications become available. Strong tools for prevention of cognitive decline are already available to all of us: physical and cognitive activity, healthy diet, and disease management. Evidence from studies such as the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability are already showing that lifestyle changes can improve cognitive performance. Let’s spread the word and promote healthier aging!

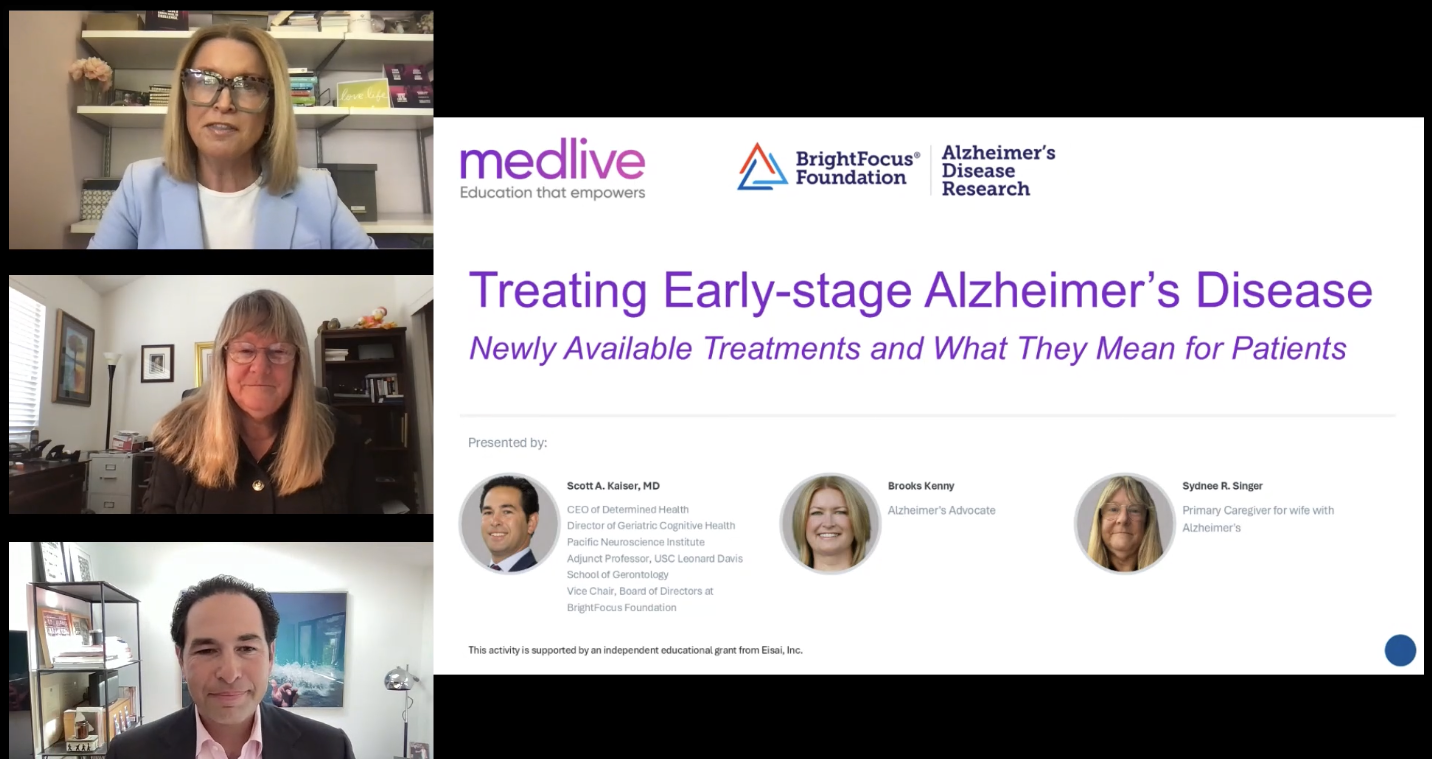

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Through its flagship research programs — Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research— the Foundation has awarded nearly $300 million in groundbreaking research funding over the past 51 years and shares the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Lifestyle

- Prevention