Learn more about a sleep-related condition that can increase the risk of developing dementia, heart attack, and stroke.

It took a fender bender to bring Bill* to his primary care clinician for evaluation. “Maybe I snoozed! I woke up on the embankment and I’m lucky nobody was hurt.” In addition to driving difficulties, Bill also described increasing forgetfulness, fatigue, and confusion over the past year. Despite his young age of 65, Bill’s primary care physician referred him to the Memory Clinic, where additional history was obtained. Bill reported that his mood was low, his weight was increasing, his blood pressure was out of control, and he was constantly dragging. He usually couldn’t get through the day without sneaking a nap. He and his wife agreed that he was spending plenty of time in bed each night. Bill’s wife admitted that she sometimes would move to the living room recliner because of Bill’s loud snoring and gasping.

*The name and details were changed to protect privacy.

Bill’s little motor vehicle accident was a blessing in disguise. He was referred for a sleep study which revealed severe obstructive sleep apnea, a potentially treatable medical condition. Bill was suffering from a common disorder that, like radio drama’s famous Shadow, has “the power to cloud men’s minds.” And women’s minds, too, although researchers think women’s higher progesterone levels may stimulate breathing and reduce the likelihood of apnea. Sleep apnea is considered a risk factor for dementia. People with sleep apnea have been shown not only to have impaired memory and executive function, but also biomarker changes that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

What is Sleep Apnea?

Sleep apnea, which means failure to breathe during sleep, can be obstructive or non-obstructive. Non-obstructive or “central” apnea occurs when the brain fails to signal the breathing muscles that it’s time to get active. In obstructive apnea, breathing fails because of a relaxed airway that fails to open up despite the brain’s insistence. Eventually, sometimes after more than a minute without breathing, the brain sounds its alarms urgently enough to jolt the muscles of breathing back into action. Sometimes this wakes the sleeper, but more often the periods of apnea and gasping serve only to rob sleep of its restful and restorative quality. A respiratory infection or excessive alcohol use can also interfere with breathing during sleep. Chronic and severe apnea, however, is a prolonged, debilitating condition.

Risk Factors for Sleep Apnea

Older age, with its loss of muscle tone, is an important risk factor for sleep apnea. Men have sleep apnea more often than women, although women can also be affected. Obesity, smoking, excessive use of sedatives or alcohol, or a positive family history of sleep apnea are additional risk factors. Also, more than half of people with Down syndrome have sleep-related breathing problems.

The Risks of Untreated Sleep Apnea

One of Shakespeare’s characters called sleep the “chief nourisher in life’s feast.” He was right! During sleep, the body actively repairs and restores itself. Lack of oxygen during sleep interferes with memory formation, blood pressure regulation, and weight control.

Untreated apnea is associated with increased risk for dementia, stroke or heart attack. In one study, persons with sleep apnea had a 30 percent higher risk of heart attack or death than those without apnea.

The Connection Between Sleep and Alzheimer’s

Some studies have shown an association between sleep deprivation and increased levels of two Alzheimer’s disease-related proteins in the brain (beta amyloid and tau). In addition, difficulty sleeping is common in people with Alzheimer’s disease. There may be a bidirectional relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and the quality and duration of sleep, but more research is needed.

Diagnosing Sleep Apnea

The current gold standard for diagnosing sleep apnea is a sleep study (polysomnography). This is a painless procedure during which measurements are made of your heart rhythm and rate; respiration; leg movement; oxygen and carbon dioxide levels; brain waves; and chin and eye movements.

Treatment for Sleep Apnea

Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea can be more straightforward than treatment of apnea that is central or mixed (with both central and obstructive problems). Simple steps such as limiting alcohol, smoking, sedatives and muscle relaxants; losing weight; sleeping on one’s side (sometimes reinforced by sewing a tennis ball on the back of the pajamas or wearing a “fanny pack” to bed) or elevating the head of the bed can help. Physical training has been shown to reduce sleep apnea even in the absence of weight loss.

CPAP Machine

Bill’s apnea was serious enough to require more intensive treatment, so he was prescribed continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), a treatment that uses an air pump, tube, and mask to inflate the sleeper’s collapsed airway. Testing of patients has shown that CPAP reduces the neuropsychological deficits associated with sleep apnea.

BiPAP and Auto CPAP

If CPAP had been too uncomfortable for Bill, as it is for some people, he would still have treatment alternatives. Variable positive airway pressure (BiPAP), and “Auto CPAP,” are better tolerated by some because they respond to the sleeper’s natural breathing to fine-tune the delivery of air through the mask.

Special Dental Appliances

Specially trained dentists can treat apnea by preparing a retainer-like device that pushes the lower jaw forward in order to keep the airway open.

Surgical Procedures

Although obstructive sleep apnea can usually be managed satisfactorily without surgery, more aggressive treatment appears to be warranted and effective in some individuals. The results of surgical procedures designed to open the airway have been somewhat mixed. A recently approved implantable device opens the airway by stimulating the hypoglossal nerve (a cranial nerve that activates certain muscles of the tongue), causing the tongue to contract intermittently.

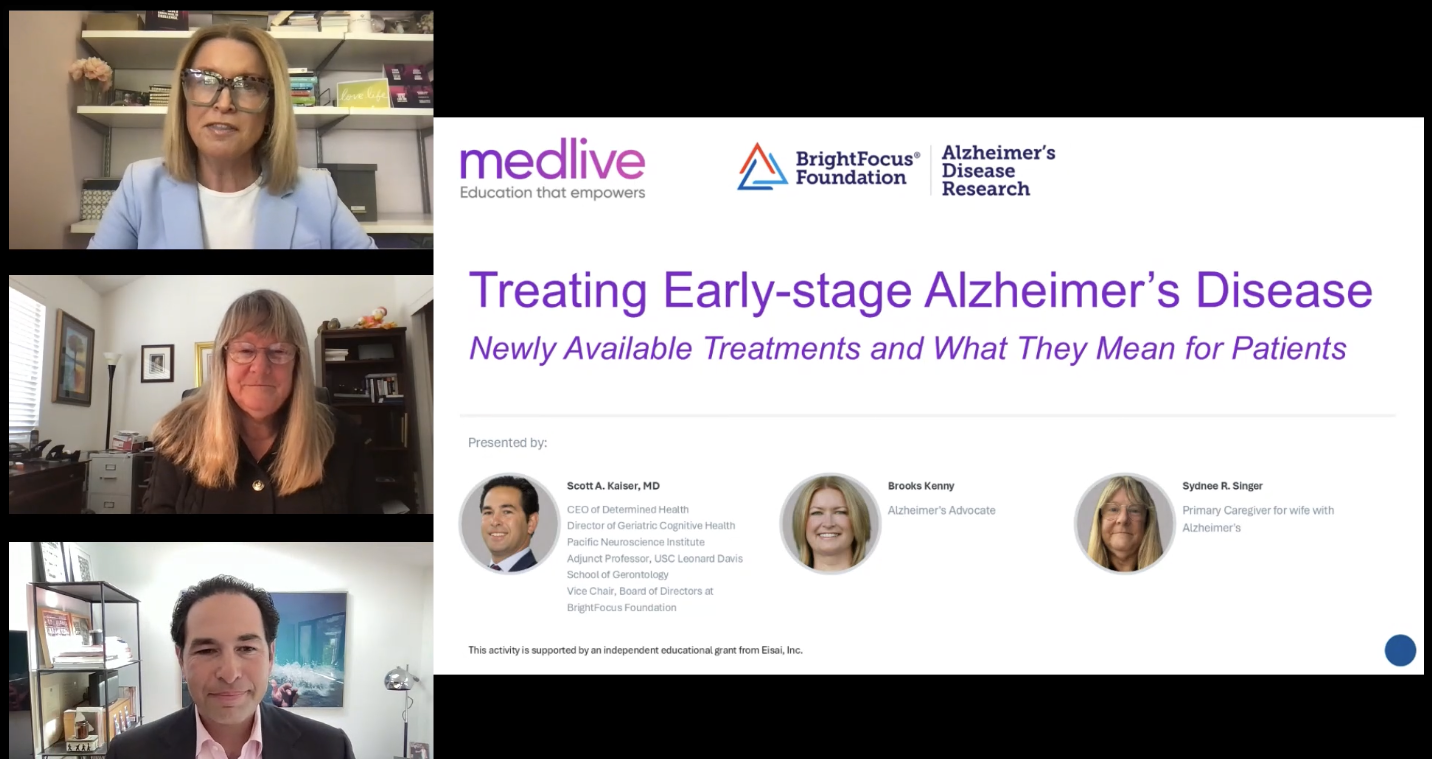

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Through its flagship research programs — Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research— the Foundation has awarded nearly $300 million in groundbreaking research funding over the past 51 years and shares the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Risk Factors