Learn why the decline in memory can be so different between people of the same age, even among closely-related individuals.

Andrew accompanied his father, Robert, to the memory clinic. Our evaluation found that Robert had a major neurocognitive disorder, probable Alzheimer’s disease, and that his memory and executive function were quite impaired. Andrew was not surprised when we made this diagnosis, but he was upset about his father and also asked about his own risk for dementia. He said, “My Uncle Walter is 85 and still makes rounds at the hospital every day. His patients say he is still as sharp as he ever was. But my father is only 76 and can’t remember how to drive to the grocery store! How can these brothers have aged so differently? Is there any way I can age like my uncle instead of like my dad?”*

*Andrew, Robert, and Walter are similar to many people seen in a Memory Disorder Clinic, but they are composite characters rather than individuals for the protection of privacy.

Why does memory decline differ so much between people of the same age, even among closely-related individuals? How do some brains resist the damage caused by aging, injury, or dementing diseases more successfully than others? Researchers looking at imaging studies or autopsy results have tried to understand how one person with mild evidence of brain damage can be severely disabled while another with extensive brain changes shows only mild cognitive impairment.

Even among people who have sustained a head injury or a stroke, cognitive symptoms and cognitive recovery differ greatly. Some brains just seem to be stronger and more resilient in the face of aging or destructive events. “Cognitive reserve” is an important idea that sheds some light on this mystery.

What is Cognitive Reserve?

The main idea of “cognitive reserve” is that some brains keep on working more successfully than others despite similar degrees of destruction or degeneration, and that this is the effect of innate and acquired brain characteristics. At birth, our brains already differ. Some are larger, some smaller. Some have greater specific or general intellectual potentials. But lifetime experience, education, occupation, nutrition, and medical health all exert game-changing influences during our lives.

These differences are believed to reflect the quality of the brains’ internal connections and health. A healthy, well-developed, well-nourished brain, and a medically healthy body work more efficiently. It also resists the effects of injury from trauma or stroke, or compromise associated with diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or depression.

The Positive Effects of a Stimulating Environment

During childhood, a cognitively stimulating environment promotes the development of larger brain volume. Physical exercise and cognitive stimulation increase molecules that enhance the brain’s ability to change continuously throughout an individual’s lifetime. This is called brain plasticity. In addition, these molecules also promote the development of structures that permit nerve cells to pass an electrical or chemical signal to other nerve cells, called the synapse.

A healthy brain in a stimulating environment is growing new cells and making new connections. The combined effects of intellectual endowment, education, experience, and occupation appear important influences on how a damaged brain will compensate and preserve functioning. The decline in memory, executive function, and language skills associated with normal aging is slower in people with greater literacy.

In one important study, for example, people with low education and low lifetime occupational attainment were nearly three times as likely to develop dementia when compared to their better educated and more accomplished peers. Even when pursued later in life, engagement in cognitively-stimulating leisure activities has been demonstrated to increase resistance to clinical dementia. The theory of cognitive reserve has led researchers to discover that a more highly-trained brain is able to use its resources more efficiently and to recruit additional brain areas more readily when needed.

A Paradox

It may seem paradoxical, but the idea of cognitive reserve may also help us understand why dementia in more highly-educated people can progress more quickly once it becomes apparent. There may be a threshold of damage that even the most highly-developed brain cannot overcome. Though a brain with greater reserve fights off dementia’s effects longer, exhaustion of the cognitive reserve typically leads to more rapid deterioration because the underlying destruction has already been more extensive than the clinical appearance would have suggested. Even among healthy older adults, memory decline develops later but then progresses more quickly in those with higher education.

Helpful Advice for Developing and Maintaining Brain Health

What advice was there for Andrew as he looked ahead to his later years? One of the most important things about the theory of cognitive reserve is that it gives us hope for fighting the effects of brain aging and degenerative disorders even though we have not yet been able to discover medications that cure dementia.

Early education, cognitive stimulation, and physical activity set the stage for later brain health. During adulthood, continued learning and engagement in challenging leisure-time activities can strengthen resistance to cognitive decline.

Brain health is further supported by physical activity and good self-care, which includes adequate sleep and stress-reduction, good nutrition, and care of medical health.

Individual genetic factors that affect risk for dementia are as yet unmodifiable, but the progression and expression of brain aging and disease are strongly affected by how we live and how we use our brains. Andrew, young enough to increase his physical and cognitive activities, is in a position to improve the long-term outlook for his cognitive health in later years.

As we learned more about Andrew’s family, it became clear that Walter and Robert had lived very different lifestyles. Walter attended college and graduate education and was a successful medical specialist who liked to engage in cognitively challenging hobbies and lifelong learning. Robert had finished high school but left college during his freshman year in order to support his aging parents in their family business. He was a hard worker, a good provider for his family, and a beloved man in his community. But he habitually neglected his physical health and leisure activities. As he aged, his lifestyle became more sedentary, and he preferred to use his limited free time for relaxation rather than cognitive stimulation or physical exercise. He developed several chronic medical disorders, high blood pressure, and diabetes, and his attention to their management was not a priority. This may have accounted in part for the brothers’ very different experiences in aging. Beyond whatever differences were due to genetics, Walter seems to have developed a greater level of cognitive reserve. Walter exercised his mind and body and cared for his medical health more consistently than Robert did. This lifestyle difference may partly explain why Walter’s mind continued to function at a high level while Robert’s was declining.

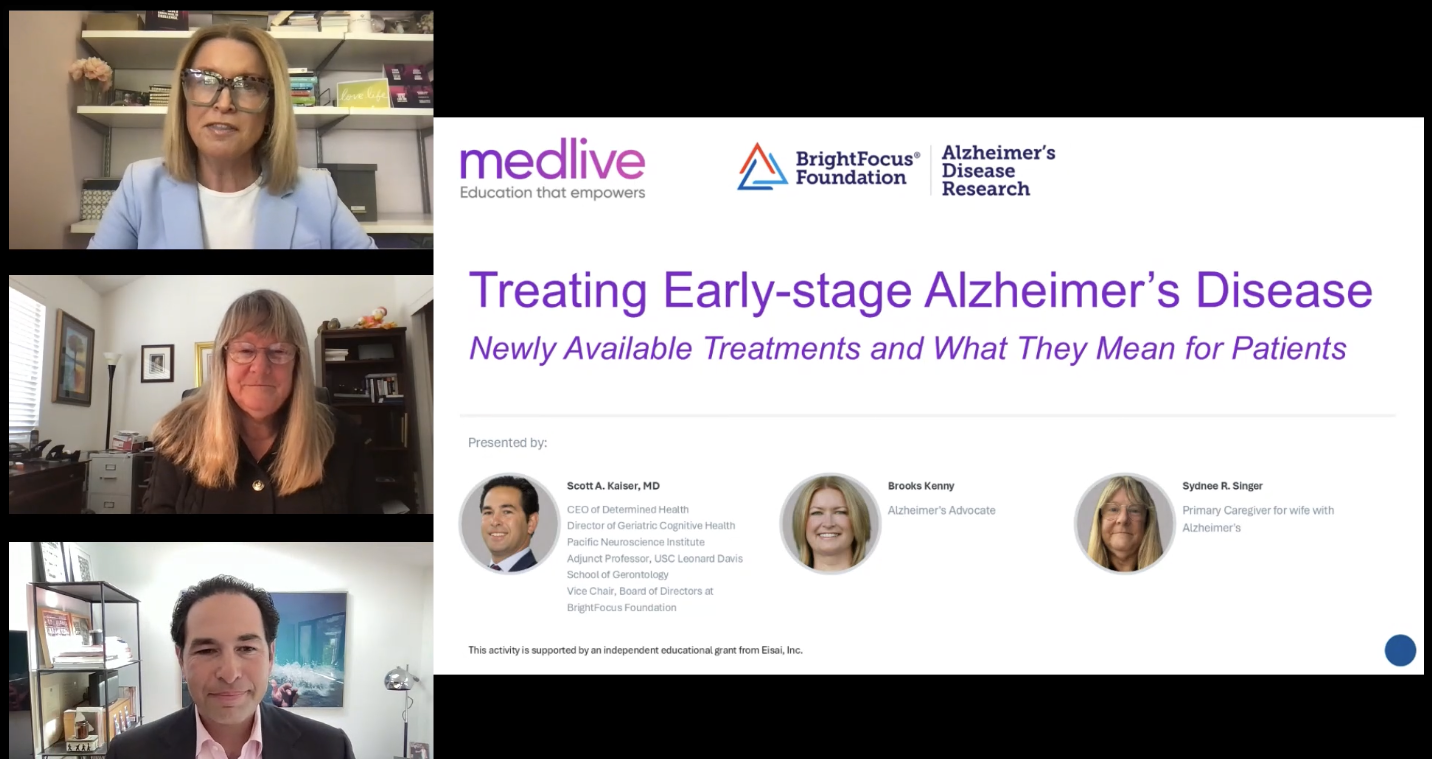

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Through its flagship research programs — Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research— the Foundation has awarded nearly $300 million in groundbreaking research funding over the past 51 years and shares the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Brain Health

- Genetics

- Lifestyle

- Risk Factors