Learn how microorganisms that live in our gut may influence physical and cognitive health.

What is a Microbiome?

The next time you feel lonely, consider this fact: Your body is teeming with guests; about a thousand different species of bacteria, fungi, and viruses living on your skin and inside your digestive system. Your colon is “colonized” with some 10 trillion of these critters. Together they contain as many cells as your body and weigh as much as your brain. Together, they are referred to as your “microbiota,” and their collection of genes is called your “microbiome.” Your microbiome, which contains more than a hundred times as many genes as your own DNA, is not something to ignore.

The Microbiome-Health Connection

Researchers are showing that the microorganisms in our gastrointestinal systems affect a surprising number of health conditions including type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, obesity and food cravings, allergies, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, and even Alzheimer’s disease.

Our Modern Lifestyle

Urbanization and our modern dietary habits have changed the composition of our intestinal bacteria, reducing its diversity and promoting the growth of a species, called Bacteroides, which thrive on our meat-rich diet. Excessive intake of artificial sweeteners and frequent use of antibiotics are two other factors that affect the composition of our microbiota. Unhealthy shifts in the population of intestinal bacteria, unfortunately, can affect the whole body. Researchers have identified multiple ways in which our bacterial inhabitants can affect overall health.

“Leaky” Gut

One might assume that “what happens in the gut stays in the gut,” or at least until it’s properly eliminated. But changes in the microbiota can result in a “leaky gut” that permits the exit of microorganisms and compounds that are a result of their metabolism (metabolites) into our bodies’ circulation. This may have far-reaching effects on the chemistry of our bodies.

Microorganism metabolites, for example, can be a force for good or evil. Some microbial metabolites may be helpful. Gamma amino butyric acid (GABA), for example, is a stress-relieving compound, a sort of natural tranquilizer, that can be infused into our systems as a consequence of bacterial metabolic activity. On the other hand, scientists have found evidence that some unhealthy food cravings are the consequence of bacterial metabolites’ effects on the brain.

Alzheimer’s Disease

With respect to Alzheimer’s disease, the activity of intestinal bacteria may play a significant role. Intestinal flora can produce amyloid which enters the blood circulation and crosses the blood-brain barrier to gain entry into the brain. One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease is the accumulation of amyloid plaques between nerve cells (neurons) in the brain. Lipopolysaccharides, a component of bacterial cell membranes, can get into the body’s bloodstream and activate inflammatory processes which contribute to the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. A diet low in antioxidants or high in pro-inflammatory fatty acids can facilitate these microbiotal consequences.

Reducing Risk

How can we use what scientists have learned about the microbiota to reduce our risk of Alzheimer’s disease? One important message is that our microbial inhabitants need us to feed them properly. The same diet that has been shown to reduce Alzheimer’s disease risk, the Mediterranean Diet, has also been found beneficial for our microbiota. A plant-based diet rich in fruit and vegetables and high in fiber changes the composition of our flora, shifting the population away from Bacteroides bacteria and encouraging the growth of health-promoting Prevotella species. These same undesirable Bacteroides species are inhibited by consumption of the polyphenols in green and black tea. Prebiotics (nondigestible substances that can act as food for the gut microbiota) provide additional support for a healthy microbial population. Prebiotic fiber, although indigestible by a human, is a source of food for the microbiota that promotes the growth of healthful microorganisms such as bifidobacterial and lactic acid bacteria.

Summary

When the great poet, Walt Whitman, wrote “I contain multitudes,” he probably was not referring to his intestinal flora! However, each of us does, in fact, serve as home to trillions of organisms that influence our metabolism, immune function, weight, and even cognitive health. The Mediterranean Diet has been shown to reduce the risk for Alzheimer’s disease, and the health of our microbiota may be one of the reasons why this diet is so beneficial. Feed your microbiota lots of fiber, fruit, and vegetables! This is one of the ways in which you can improve your health, reduce systemic inflammation, and even, perhaps, reduce your risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

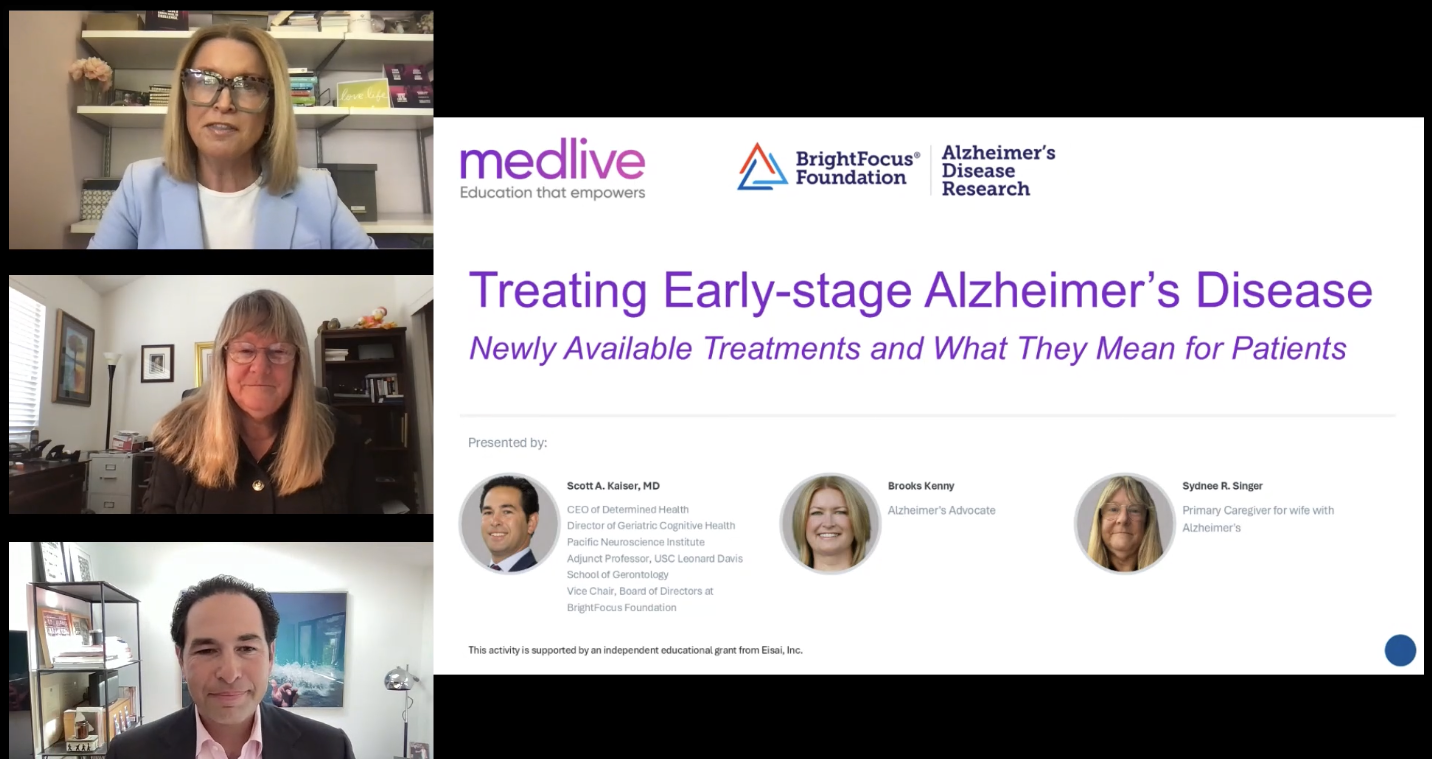

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Through its flagship research programs — Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research— the Foundation has awarded nearly $300 million in groundbreaking research funding over the past 51 years and shares the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Nutrition

- Risk Factors