New research has shed light on the connection between attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and Alzheimer’s, two neurological conditions that manifest in very different ways.

One study showed that people who are genetically predisposed to ADHD may be more likely to develop cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

Although this connection has been suspected for some time, the study is the first to tie the genetic risk of ADHD to the development of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. It was published by University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine researchers in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

“Understanding the risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease is crucial for prevention and for closely monitoring those who are more susceptible and at higher risk,” said Tharick Pascoal, MD, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry at the university and senior author of the study.

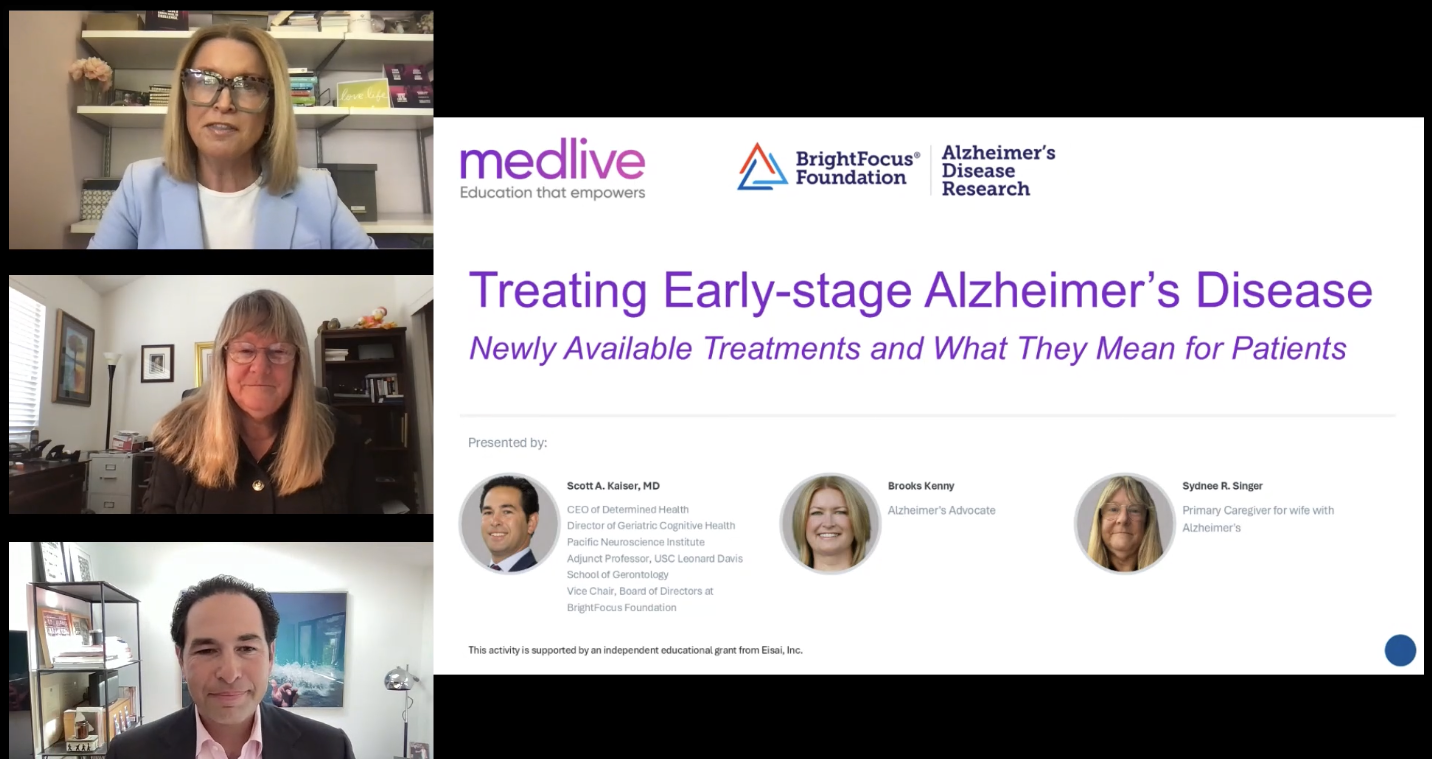

Another study, conducted by researchers at Imperial College London and published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, showed that noradrenergic drugs prescribed for ADHD, such as Ritalin and Concerta, may effectively improve cognitive symptoms in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Noradrenergic drugs change the levels of brain chemicals in people with ADHD to improve attention and other symptoms. In people with Alzheimer’s, they showed a small but significant effect on cognition, according to the researchers.

In both studies, the authors stated that follow-up trials are needed to better understand the connection between ADHD and Alzheimer’s and which types of drugs are most likely to be most effective.

ADHD Symptoms in Children and Adults

ADHD is considered a childhood disorder, but in many cases, it can persist into adulthood. In children, symptoms include trouble paying attention or staying focused, problems finishing a task, losing items, getting easily distracted, and being forgetful.

In adults, symptoms include impulsiveness, disorganization, poor time management, excessive restlessness, frequent mood swings, and problems coping with stress. These symptoms can be more subtle in adults, which may make it challenging to diagnose.

ADHD as a Risk Factor for Alzheimer’s

The University of Pittsburgh researchers used a database of 212 adults ages 55 to 90 with no diagnosis of ADHD or cognitive impairment. The data included brain scans, baseline levels of the brain proteins amyloid and tau, and the results of cognitive assessments over six years, as well as the patients’ genome sequences.

There is no single gene that determines whether a person will develop ADHD; rather, it can be derived from a series of small genetic changes. To measure risk, the researchers used an existing tool called ADHD polygenic risk score, or ADHD-PRS.

By calculating each patient’s risk score and comparing it with any signs of Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers were able to show that a higher ADHD-PRS was associated with greater decline of cognitive function and the development of Alzheimer’s over time.

Looking to the Future

Dr. Pascoal pointed out that because there are no large studies that followed children diagnosed with ADHD into adulthood, they could not rely on clinical diagnoses of the condition. “What we don’t know is if a patient is medicated their whole life and is stable with no ADHD symptoms, do they also have a higher risk or not,” he said. “If we treat ADHD, does that lower risk?”

The next step in his team’s research is a study involving people in their 40s who had been followed since they were diagnosed with ADHD as young children. They will be followed for 15 to 20 years to learn more about the connection between the clinical diagnosis of ADHD and the risk of Alzheimer’s.

It may take many years to come up with more definitive answers.

“For now, I would say that young adults with ADHD should not be overly concerned, and older adults who begin to experience cognitive symptoms that start to get in the way of familiar tasks should behave like anyone else experiencing these symptoms,” Dr. Pascoal said. “They should see their medical provider and not just write off any cognitive symptoms they may be having as a normal part of aging.”

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Through its flagship research programs — Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research— the Foundation has awarded nearly $300 million in groundbreaking research funding over the past 51 years and shares the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Brain Health

- Risk Factors