This article discusses recent findings concerning the burden that Alzheimer’s disease imposes on the African American community, and some of the recommendations that are being made in order to address this disparity.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause of severe memory loss and dementia among older adults, is a risk for everyone in our aging population. By age 85, nearly half of older adults in the U.S. are affected. Research has identified some health conditions and genetic factors that appear to increase risk.

Until recently, race, as one of the important risk factors, went unrecognized. Now, however, we know that African Americans in the United States carry more than their share of the suffering and expense associated with AD. This article will discuss the burden of AD on the African American community and some of the recommendations that are being made to respond to this very grave threat.

Why the Disparity?

The development of AD is often associated with the presence of risk factors that might increase vulnerability to the disease, and African Americans are disadvantaged by having a significantly worse risk factor profile for AD. The principle gap between whites and African Americans can be explained by the presence of one or more medical conditions that coexist in addition to Alzheimer’s disease; environmental factors; and genetic factors. Each of these is discussed below.

- Medical conditions: Among the most significant indicators for increased AD risk are the so-called “vascular risk factors,” meaning medical conditions that impact the blood vessels. These have been more common among African Americans than among whites. Poor circulation (sometimes called vascular disease), stroke, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes mellitus are more prevalent among African Americans than among whites. These disease patterns also are reflected in the greater prevalence of vascular dementia among African Americans than whites. Each of these risk factors is very treatable, and mid-life recognition and treatment of vascular risk factors may be important tools in reducing AD risk.

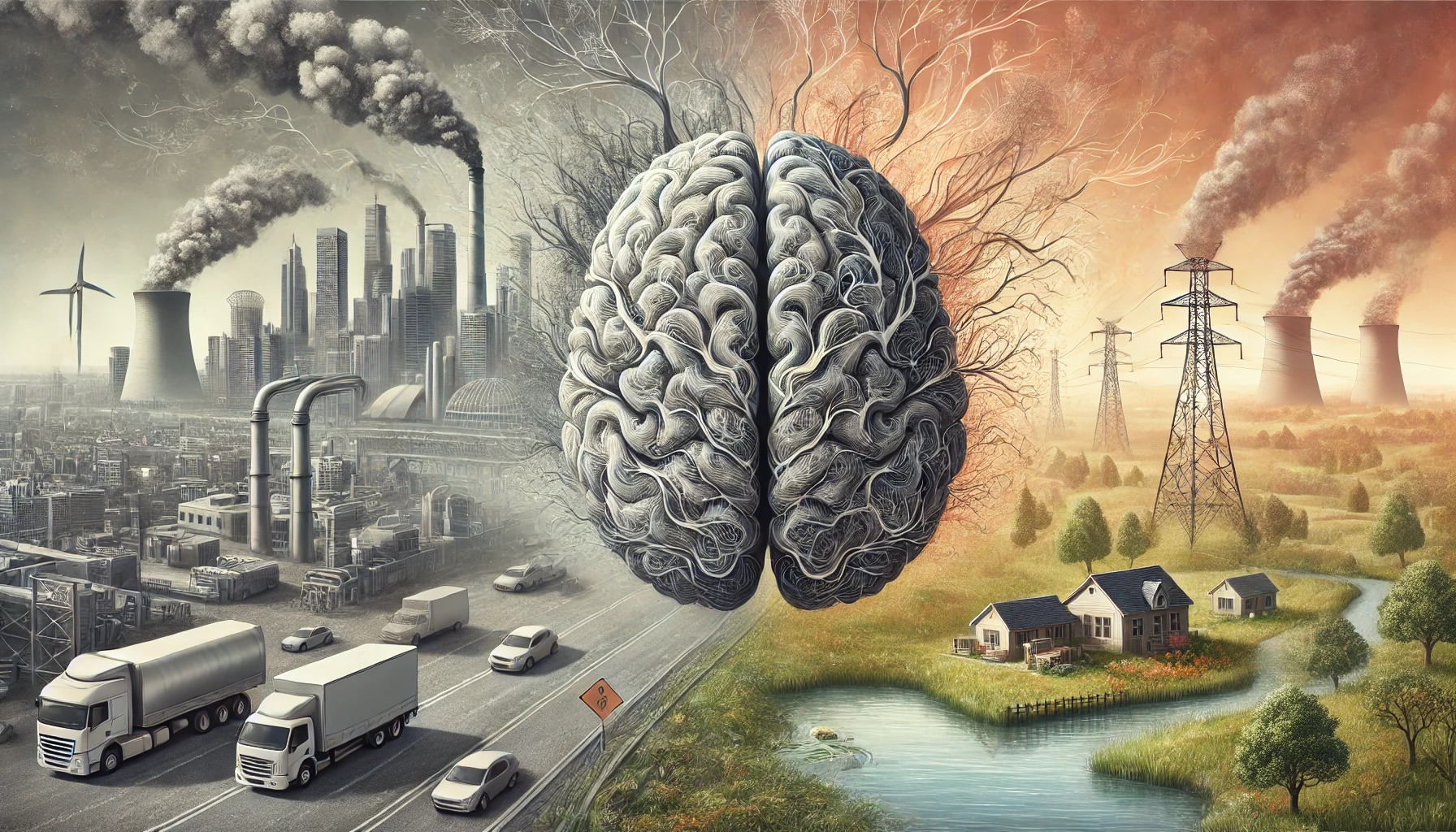

- Health Care Disparities and Social Determinants of Health: The likelihood of developing AD is inversely related to educational achievement and income. African Americans’ ranking in these two metrics is rising but is still historically lower than whites. These sociocultural factors may contribute to their higher risk of AD. These social determinants are also manifested in available occupations and residential choices. Certain occupations are associated with greater health hazards and some lower-income residential areas may be associated with greater exposure to air pollution, now recognized to increase later risk for cognitive decline. Access to health care, too, is affected by income, educational level, and residential location.

- Hereditary factors: The impact of various genetic risk factors for AD may be different among African Americans than for whites. For example, some studies have shown that the presence of the genetic mutation called ApoE4 added less additional risk for African Americans than for white participants in the study.

What Can Be Done?

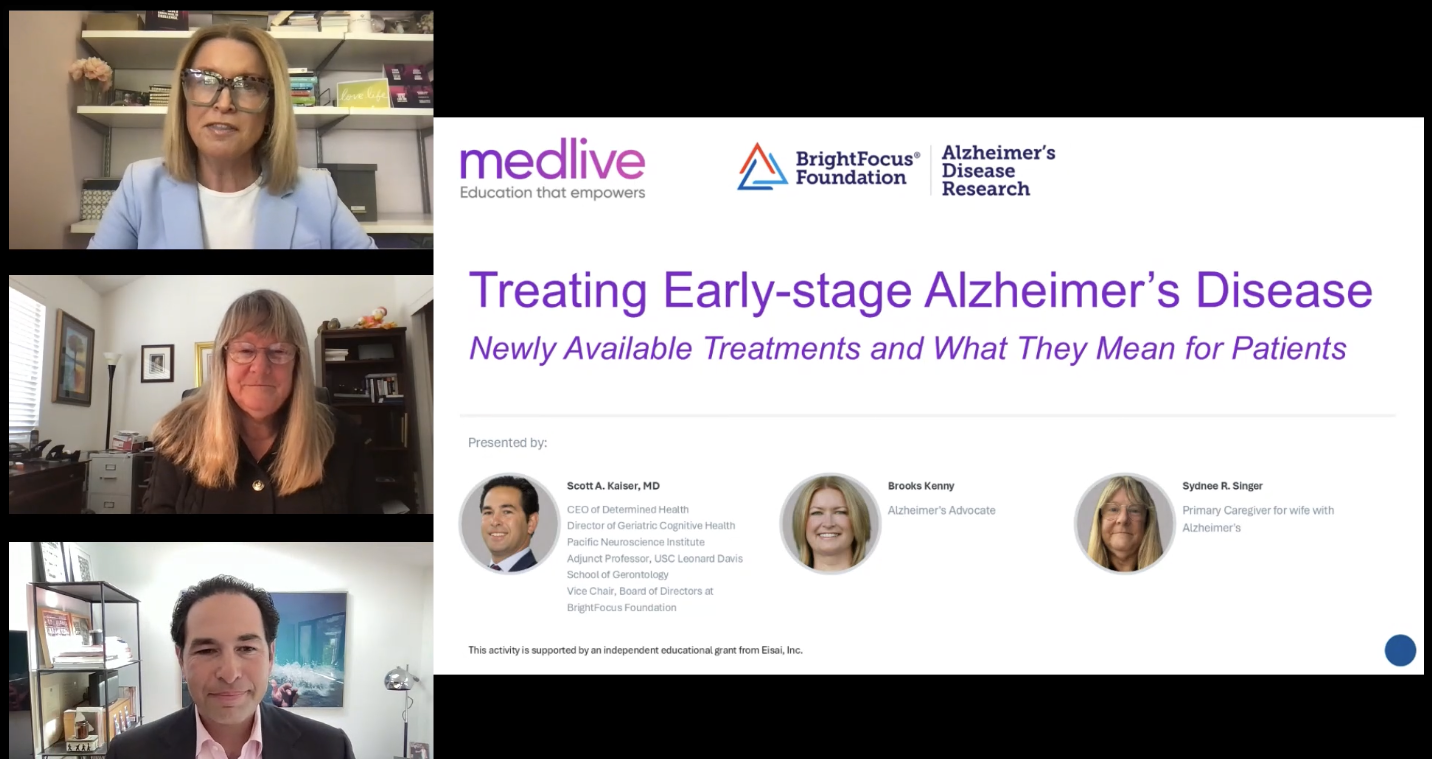

Access to diagnostic assessment, preventive care, and consultation with medical specialists is unequal among various populations in our country. Without equal access, the differences in recognition and treatment of AD cannot be addressed as effectively.

Detection is the first step necessary to bring about the benefits of early treatment for AD. Researchers have expressed concern that some detection tools in use are inherently biased with respect to ethnocultural factors and therefore not equally useful across different populations tested. The biases in the tests are more likely to falsely label cognitively healthy adults as impaired than to mistake an affected person for normal. However, this small false positive effect may be overshadowed by a more important issue of underreporting of cases, leading to diagnosis at a later disease stage, when treatment is less effective.

Finally, there are shortfalls to our body of research into AD. All too often in the past, research has been conducted in populations that were easy and convenient to enroll in studies, and in many cases without regard to the need to explore differences in vulnerability, pathology, and treatment among diverse populations. As a result, African Americans are underrepresented in clinical trials of AD medications, requiring us to assume or guess whether race and other differences in AD treatment populations might have an impact on their treatment response and prognosis. We must all advocate both for more research on AD and especially for specific investigations into the effects of AD treatments on African Americans and other at-risk populations.

Never before in history have there been opportunities like those afforded in our era thanks to the advances in medical technology, clinical evaluation expertise, and new treatments. We must advocate for all to have access to the fruits of these advances: that means preventive care, including the adoption of a brain-healthy lifestyle; early detection; and research that takes into account the needs of special populations.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Through its flagship research programs — Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research— the Foundation has awarded nearly $300 million in groundbreaking research funding over the past 51 years and shares the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Health Equity

- Risk Factors