Both COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s are having an exaggerated impact on elderly communities of color. Learn why that’s the case, and gain insights on handling this crisis as best practices are developed.

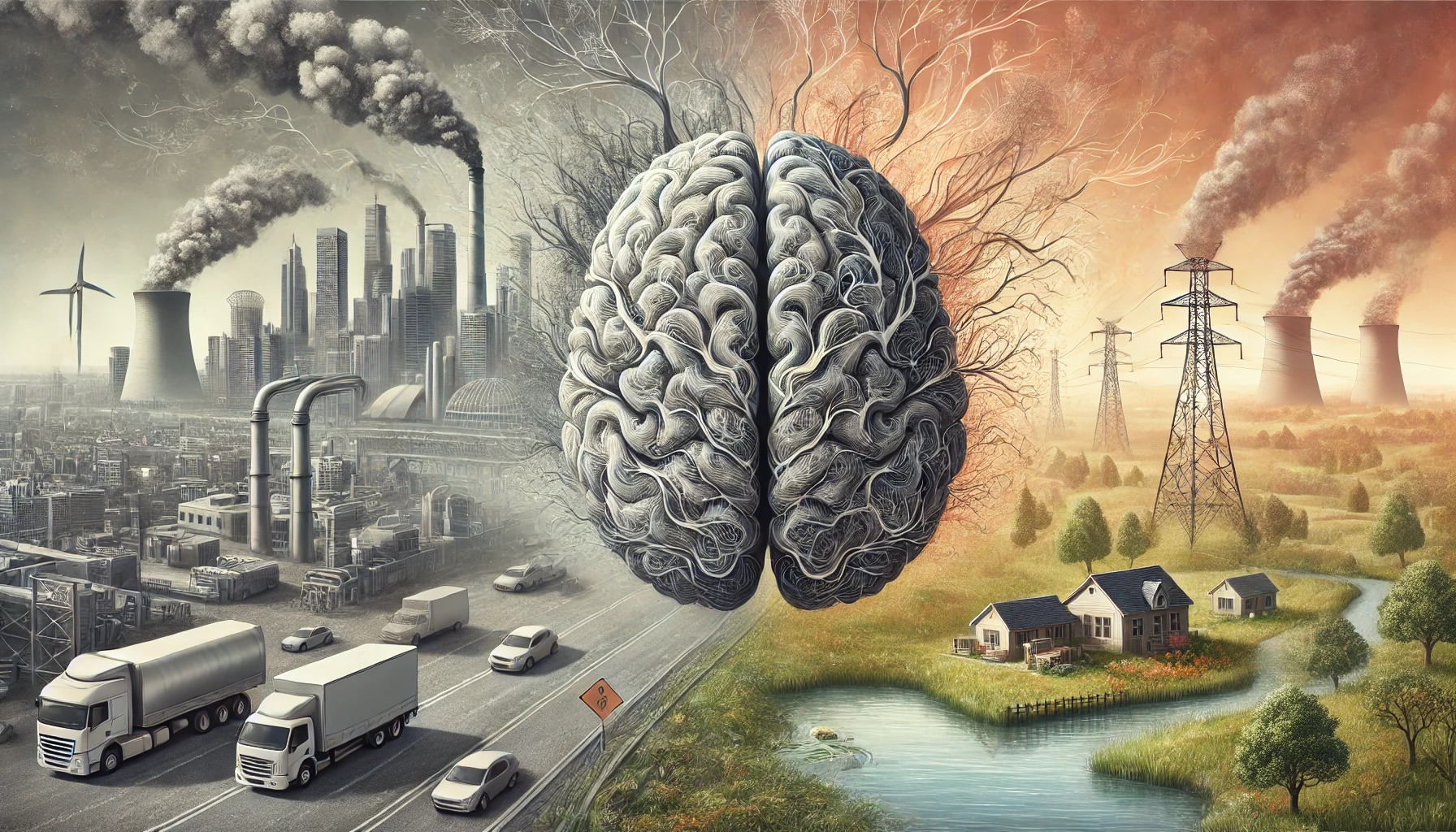

COVID-19 has profoundly impacted the elderly population. Although Alzheimer’s disease (AD) does not appear to increase an individual’s risk of contracting COVID-19, Alzheimer’s has had a significant effect on a population that suffers from additional underlying illnesses, which can complicate the clinical manifestation of the virus. What has been particularly notable is COVID-19’s effect on elderly communities of color diagnosed with AD.

Communities of Color Have an Increased Risk of COVID-19 Infection

Particularly disturbing are statistics showing higher rates of mortality due to COVID-19 among African American and Latino populations. There are many reasons for this disparity that include limited access to preventative healthcare, limited healthy food options, and the fact that minorities are often working in jobs that are deemed “essential.” The last point is particularly salient as being an essential worker increases the risk of contracting COVID-19 through exposure.

Alzheimer’s Disease and Communities of Color

To better understand the impact of COVID-19 and AD on communities of color, it is important to explore the disproportionate morbidity and impact of Alzheimer’s amongst both African American and Latino populations. According to an article written by former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher, MD, and William Vega, PhD, (2017), statistics show that compared to white Americans, African Americans are twice as likely and Latinos 1.5 times as likely to develop AD. Furthermore, between 1999 and 2014, the rates of AD increased 99 percent for African Americans and 107 percent for Latino populations, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). What these statistics show is that together, AD and COVID-19 represent a huge threat that is disproportionately affecting communities of color.

Insights for Communities of Color Impacted by Alzheimer’s Disease and COVID-19

Although we do know that COVID-19 does not discriminate based on gender, race or socio-economic status, this virus may pose greater challenges to minority populations that are already dealing with Alzheimer’s and other chronic illnesses. Best practices are early in development and will evolve as we learn more about COVID-19.

In the meantime, as we await consensus guidelines, there are ways to support particularly vulnerable communities that are dealing with these two very serious health epidemics. From my experience working with minority communities and AD, I’ve learned that cultural sensitivity is important and can provide vital clues to necessary action. One cultural norm for both African Americans and Latinos is that caregiving for a loved one with Alzheimer’s is often done in the home. Therefore, minority caregivers will require support as they navigate the care needed for a loved one with limited cognitive capacity who is at increased risk for contracting COVID-19.

It is also often the case in minority communities that multiple family members provide “in-home” care for a loved one with Alzheimer’s. While in many ways a “plus,” that situation also places everyone – the individuals with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers — at increased risk of exposure. Caregivers will need to remain vigilant of other caregivers and take precautions to protect the health and well-being of family members and all who care for and/or come into contact with their loved one. It may be best to limit the number of family members to reduce potential exposure. When feasible, wearing masks and/or gloves, maintaining physical separation as much as possible, and frequent handwashing, including before/after meal preparation, bathroom visits, and other physical contact, have been shown to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission. In addition, Alzheimer’s individuals and caregivers are encouraged, and in some states required, to wear masks when venturing outdoors and into public spaces.

Another important point for minority caregivers providing care to a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease will be to ensure that other illnesses, such as hypertension, diabetes and high cholesterol, are being managed. Managing underlying illnesses is critical to maintaining a strong immune system, which is important to staving off COVID-19.

Finally, it will be important to try and maintain as much of a consistent schedule as possible during the pandemic. Medication, meals, and activities at home should be kept as consistent as possible. It may also be necessary to place written reminders for your loved one to assist with maintaining hygiene and reducing exposure. Encouraging family members to visit with loved ones using various forms of technology, such as video chats and telephone calls, can foster and maintain a positive mood in people with Alzheimer’s, which is important to overall health.

Summary

As we continue to navigate our way through the COVID-19 pandemic, it is especially important to acknowledge and address the disproportionate effects of this virus on communities of color that are already dealing with Alzheimer’s disease. The more we learn about the virus, the better prepared we will be to ensure that vulnerable communities can access the support necessary to achieve optimal health outcomes. If you think you or your loved one may have COVID-19, please contact your primary care physician immediately. You can also contact your state or local health authorities for information about COVID-19 testing.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Through its flagship research programs — Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research— the Foundation has awarded nearly $300 million in groundbreaking research funding over the past 51 years and shares the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Brain Health

- Health Equity

- Risk Factors